Every traveler has experienced digestive problems. It’s statistically impossible to avoid them.

Whether you’re reading this in a bathroom, fighting for your life, or preparing for the next adventure, you’ll find all the essential information about traveler’s diarrhea in this article.

If you need quick advice, skip to the last paragraph and save the rest for when you feel well.

In This Article

This post includes affiliate links. If you choose to purchase through these links, I may receive a commission, helping me continue creating valuable content for you. This comes at no additional cost to you.

What is Traveler's Diarrhea?

Diarrhea, in general, is when three or more loose stools per day are present, usually as a result of a higher frequency of bowel movements.

For infants, this is defined as a more than 2-fold increase in the frequency of unformed stools. Just add “while abroad” at the end of the sentences, and voila, you have the definition of Traveler’s diarrhea.

When discussing this, we usually think of travelers to lower-income countries. That’s because if an American travels to Canada or a German travels to Sweden, all aspects of stomach problems will be closer to those at home. There will be a different spectrum of microbes, settings, treatments, etc.

Many slang names, such as Montezuma’s Revenge, Delhi / Bali belly, Turista, Aztec two-step, Turkey trots…, suggest how common this problem has been for travelers worldwide.

Who’s at Risk for Traveler’s Diarrhea?

I found many estimates in the literature for the number of people affected. Some say it’s 10% to 40%, others 20% to 60%. This depends on the design of each study. Suppose 30%—40% of travelers to lower-income countries suffer from diarrhea.

According to Statista, there were around 1.3 billion tourist arrivals worldwide in 2023. If we exclude Europe, the USA, Canada, and Australia, we are left with 500 million arrivals to the rest of the world. Assuming 20% of these trips are affected by traveler’s diarrhea, we’re at 100 million people.

Estimates in science journals are far more conservative at 11 to 40 million travelers yearly. That’s still tens of thousands of people a day!

Crazy. So many people pooping at the same time.

Two main factors determine how likely you are to get sick: how you travel and where you travel to. That’s one reason the estimates differ.

Backpackers are roughly twice as likely to get diarrhea compared with business travelers.

Staying in a nice hotel and spending more is a positive factor, but it has to do with the style of travel more than the establishment itself.

Younger people and people on a budget are more likely to explore, try more food from street vendors, and eat in restaurants with lower hygiene. Children are also more affected because of crawling, touching their face and mouth with their hands more often, etc.

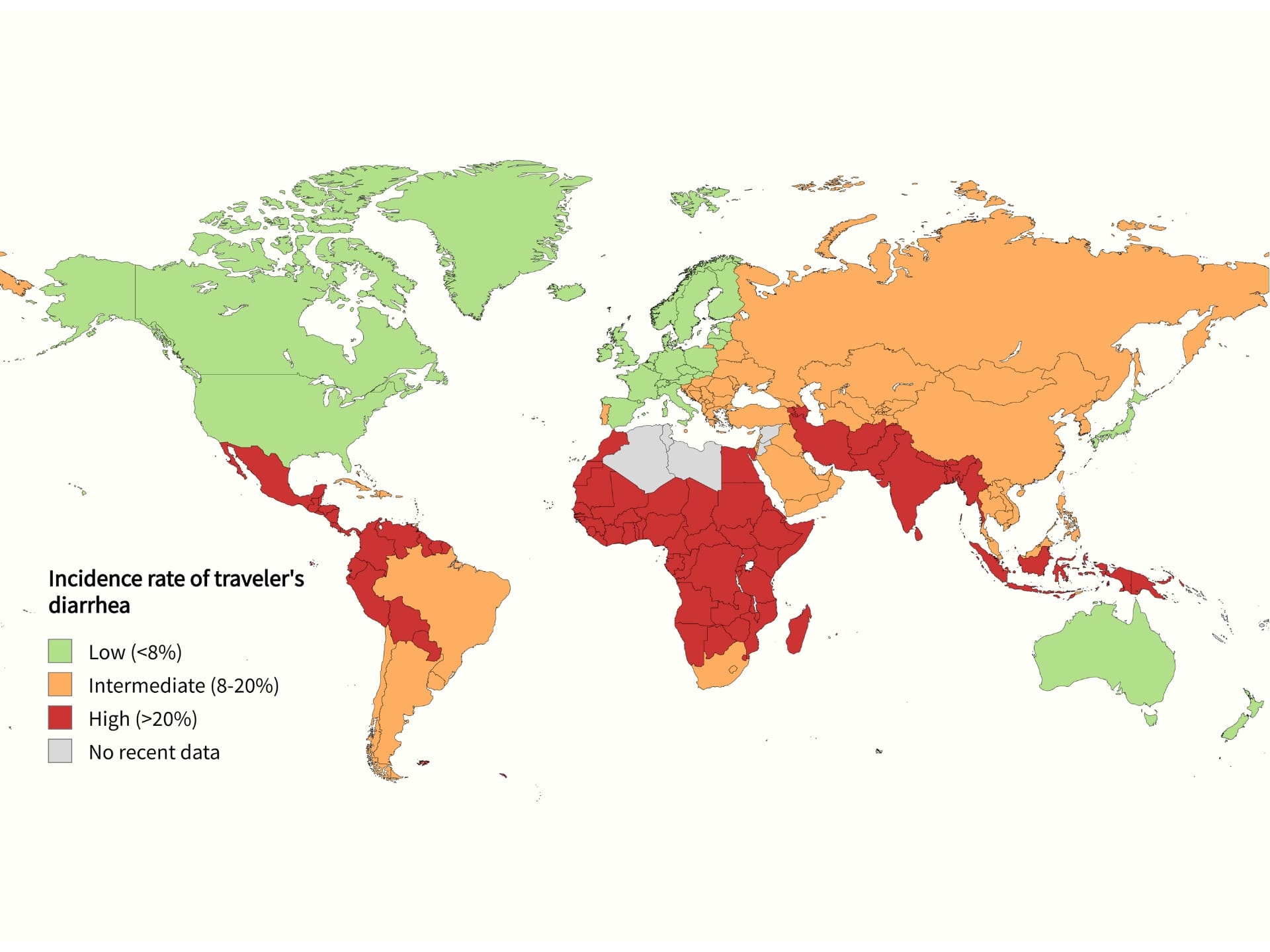

Destination is probably the most important factor.

We can divide the world into three categories by the incidence of Traveler’s diarrhea in a two-week stay.

Low-risk areas (under 8%) are the most developed countries with good infrastructure and public health control.

Intermediate risk (8%—20%) includes China, the Caribbean islands, or eastern Europe.

High-risk countries (20%—60%) include the rest; most tropical and subtropical countries are here.

Though the risk might seem high, the good news is that the incidence of traveler’s diarrhea is declining from around 65% two decades ago. It declines along with the development of each country, mostly in Southeast Asia.

Causes of Traveler's Diarrhea

However gross it sounds, pathogens responsible for traveler’s diarrhea are acquired from feces. It‘s even called fecal-oral transmission.

Along this route, there are many ways of contamination:

- bad or absent sewage system

- contaminated water

- food contaminated from soil, unwashed hands or untreated tap water

- food contaminated from other food, etc.

Most cases of traveler’s diarrhea are caused by bacteria (around 85%), viruses are second, and parasites are uncommon in causing acute diarrhea but are often found in chronic cases.

The ratio is almost the opposite in high-income countries, with viruses being the usual culprits causing stomach flu, which is often spread from person to person and has high seasonality (winter vomiting).

I won’t bore you with all the microbes’ long, tongue-twisting names. Let’s say a few important things.

E.coli is the most common cause of traveler’s diarrhea. Although it lives in our gut microflora as a good friend and neighbor, there are harmful subtypes of this bacteria. As the name suggests, Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) is not your friend.

Along with other subtypes of E.coli, you can expect these bugs in your guts around 30-60% of the time in Africa and Latin America. This number will be lower in South Asia and much lower in South East Asia.

Invasive pathogens (Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter) cause more intense symptoms, occasionally even dysentery (bloody diarrhea).

Campylobacter is very common in Southeast and South Asia. In Africa and Latin America, it‘s present in less than 5% of cases (probably more so in East Africa).

Shigella is slightly more common in Latin America, and Salmonella is common in Africa and Southeast Asia, while less common in other regions.

Parasites like Entamoeba histolytica and Giardia lamblia are found mostly in travelers to Asia but are generally not very important in acute traveler’s diarrhea.

Norovirus and Rotavirus are more prevalent in Latin America and are also typical culprits of outbreaks on cruise ships.

I need to note here that diarrhea has plenty of non-infectious causes, such as lactose intolerance, food allergy, stress, inflammatory bowel disease, medication including antibiotics, menstruation, alcohol, etc.

Traveler's Diarrhea Symptoms

Most patients have 3 to 5 unformed stools daily, but occasionally, it can be more than ten.

Symptoms present more than 70% of the time are:

- fecal urgency

- tenesmus (need to pass stools, even though the bowels are already empty)

- abdominal pain/cramps/discomfort

- nausea

Malaise, fever, vomiting, and mucus in the stool are less frequent. Bloody stool occurs in 2 to 10% of cases.

Typically, watery diarrhea and other symptoms result from increased secretion and/or decreased absorption of fluids and electrolytes by the cells in our intestines. These epithelial cells (the outer layer of the intestine) can be destroyed, invaded, or react to bacteria and/or toxins made by them.

Dysentery is a severe form of diarrhea caused by pathogens invading the intestinal mucosa (the middle layer of the intestine). This results in systemic disease with gross blood mixed with stools and/or fever.

Dysentery is seen in 3-5% of cases in Latin America and Africa and in 5-10% of cases in South Asia.

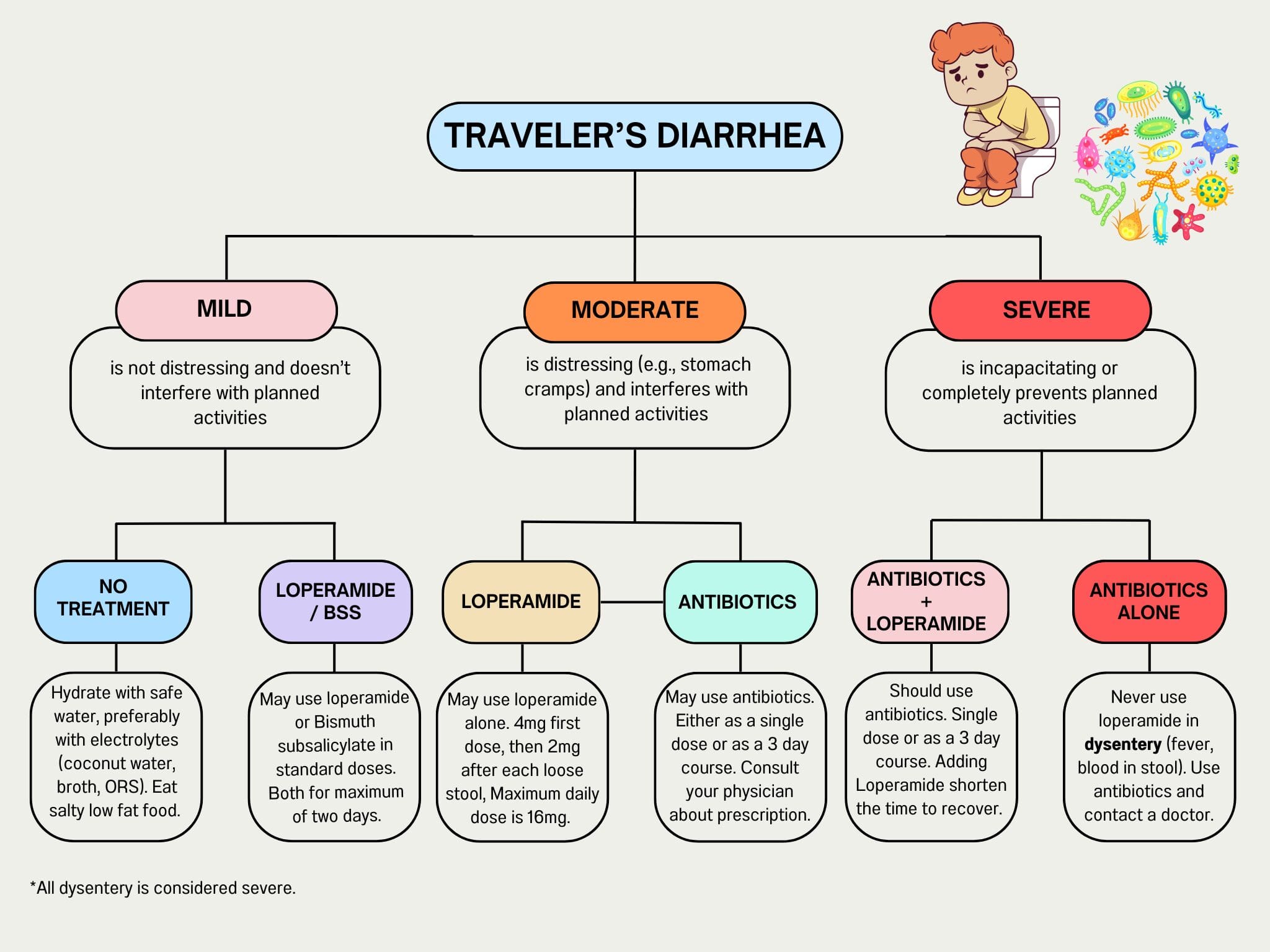

The latest guidelines recommend assessing the severity of the traveler’s diarrhea by subjective and individual observation rather than by the number of loose stools. This way, it’s easier for the traveler to self-diagnose and start proper treatment.

Mild diarrhea is not distressing and doesn’t interfere with planned activities

Moderate diarrhea is distressing (e.g., stomach cramps) and interferes with planned activities.

Severe diarrhea is incapacitating or completely prevents planned activities. Dysentery always falls under the category.

How Long Does Traveler's Diarrhea Last?

Of all the people who get sick, 90% do so in the first two weeks of travel. Most do so in the first week of travel and, statistically, most often on the second or third day after arrival.

In a Kenyan study, the probability of having traveler’s diarrhea in the first vs. second vs. third week of the trip was 36.7% vs. 9.9% vs. 3.3%. Big up for slow travel!

The average duration of untreated traveler’s diarrhea is 3 to 5 days. Mild diarrhea usually lasts less than 3 days.

With the proper treatment, this can be reduced to 1.5 half days, and using antibiotics combined with loperamide, it’s often possible to shorten the illness to just 12 hours.

If diarrhea treated with antibiotics persists or worsens after 48 hours, local medical attention should be sought.

Traveler’s diarrhea lasting 14 days or more should be properly examined, ideally in the traveler’s home country, as a special test for parasites or colonoscopy might be needed. For easier diagnostics, mention the exact area you’ve been traveling to, activities you’ve been doing, and medication you‘ve taken.

Traveler’s Diarrhea Treatment: What Works Best?

The first thing to think about when acute diarrhea hits you is to drink more fluids than usual. Your body dehydrates fast after a few watery stools, so it’s important to be one step ahead.

Drink safe bottled water, drinks that are not too sweet, fruit juice without pulp diluted with water, clear soups, or coconut water.

Avoid caffeine as it can irritate your stomach, and don’t drink or eat dairy products even a few days after getting sick, as your gut will have a problem digesting lactose.

Drink even if you’re vomiting. Try to drink small amounts frequently. This is also helpful in children. They can tolerate sipping fluids by tablespoons rather than drinking from a glass or a bottle.

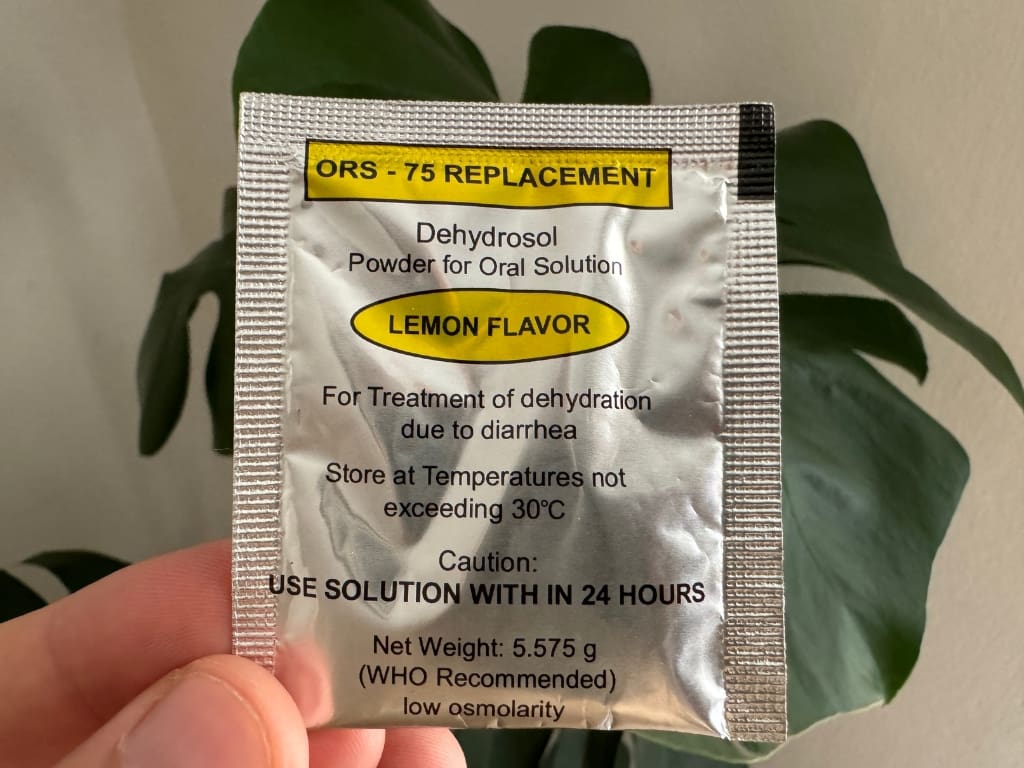

A great way to rehydrate fast is to use oral rehydration salts (ORS). They’re recommended for children and older adults but can help everyone feel better faster. They can be found worldwide in most pharmacies for a few cents. Just mix them with safe water to get those electrolytes. You can also buy them on Amazon.

It might be counterintuitive, but eating is better than fasting. Food helps to renew the cells in your gut and shortens the duration of diarrhea. Salty food low in fiber and fat is advisable.

It’s not very complicated with OTC medication. There are two options recommended: Loperamide and Bismuth subsalicylate.

Loperamide (Imodium®) is highly effective in treating mild Traveler’s diarrhea. Start with 4mg, then 2mg after each additional loose stool. Be aware that the effect can take 1 to 2 hours and persist for three days. Not being patient enough and taking too many pills can result in constipation. The maximum dose is 16mg per day. It shouldn’t be used for more than two days.

It’s the most effective OTC medicine for Traveler’s diarrhea, with an 80% success rate. It reduces the number of stools by 65%. The most common adverse effect is constipation. It’s important to say that it fights the symptoms, not the microbes.

It works by reducing the motility (movements) of the intestines. It also decreases secretion and increases the absorption of fluids in the intestine. It also reduces incontinence and urgency.

If misused, it can be dangerous, resulting in perforation or dilation of the large intestine. Don’t use it when severe abdominal pain, bloody stool, or high fever (100.4°F / 38°C) is present! It shouldn’t be used by people with acute exacerbation of IBD, in pregnancy, and in children under 2 years of age.

Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto Bismol®, Pepti-Calm®) has a wider mechanism of action with its antisecretory and anti-inflammatory properties, binding bacterial toxins, and more. Despite that, it is less effective at reducing diarrhea frequency. The success rate is up to 70% in 48 hours.

It shouldn’t be used in therapeutic dosage for more than 2 days. Main adverse effects include tinnitus (ringing in the ears), black tongue, and black stools. As the name suggests, two parts might pose a problem for a patient.

Bismuth toxicity can induce encephalopathy, including psychosis and seizures. Cases have been described when patients took large amounts of this drug for a long time or in patients with intestinal pathologies, resulting in higher bismuth absorption. This is extremely rare as more than 99% of bismuth stays in the digestive tract and is not absorbed in healthy individuals. However, because of this risk, it’s banned in Europe and other parts of the world.

Salicylates can be harmful to people with allergies (e.g., to aspirin). They shouldn’t be used in children under 12 years old, especially while having a fever, because of the risk of Rey’s syndrome. For the same reason, they shouldn’t be used by women who are breastfeeding or pregnant. They can increase the risk of bleeding when taken with some anticoagulation therapy (Warfarin).

Diphenoxylate (Lomotil) has a similar function and use case as Loperamide, but it has not been studied extensively in Traveler’s diarrhea.

Activated charcoal doesn’t work in treating traveler’s diarrhea.

Alcohol doesn’t work by „killing the bug“; it can rather further irritate the stomach.

Probiotics aren’t recommended due to a lack of data.

Racecadotril is a common medication for diarrhea. Although it’s not recommended for traveler’s diarrhea due to the lack of data, it’s a good option for children and infants because of its safety profile. It’s available in Europe and some Asian countries. It’s not sold in the USA.

Antibiotics for Traveler’s diarrhea: When should I use them?

The topic of antibiotics is highly complex, and the choice depends on other medications, allergies, the medical history of the patient, the destination, and so on. In this short text, I’ll have to simplify a lot. Always consult your physician to know what’s best for your specific situation.

The use of antibiotics (and other drugs) should be considered in the context of risk vs. benefit. Risks of using antibiotics, in general, include allergy, antibiotic-associated colitis, vaginal yeast infection, acquiring multiresistant strains of bacteria, drug-specific side effects, interactions, etc.

For self-assessment while traveling, antibiotics are not recommended for mild symptoms. They may be used in moderate diarrhea and should be used to treat severe traveler’s diarrhea.

There are three main options:

Fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin – Cipro®, levofloxacin – Levaquin®),

Azithromycin – Zithromax®

Rifaximin – Xifaxan®.

Fluoroquinolones (FQ) are the first choice for treating traveler’s diarrhea. They can be taken as a single dose or a three-day course. However, they are not recommended for use while traveling in Southeast and South Asia as levels of quinolone resistance are high (more than 90% of Campylobacter resistance in Thailand).

They shouldn’t be used during pregnancy or to treat dysentery. Common adverse effects are headache, dizziness, nausea, and diarrhea (funny, right?). Rare side effects, including tendinitis and even Achilles tendon rupture, were reported. Use in children is controversial and normally reserved for specific infections; however, a short course of FQ might be safe.

Azithromycin is a first-line treatment for dysentery and is a better option than FQ in Asia. Besides Campylobacter, It’s also more effective against Shigella spp., enteroinvasive E. coli, and others. It’s also preferred for the treatment of severe diarrhea.

It’s generally well tolerated, with occasional side effects such as diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain, and headache, typically present in a single dose regime. It can be taken as a single dose, divided in one day, or as a three-day course. It’s safe for children older than 2 years and during pregnancy.

In comparative studies, rifaximin was non-inferior to ciprofloxacin when treating noninvasive bacteria. However, it shouldn’t be used when invasive pathogens are suspected (fever, dysentery) and is not recommended for areas where these pathogens are common.

Common side effects include headache, dizziness, flatulence, and exanthema. Rifaximin is considered the safest of the three as it is not absorbed from the gut, and its influence on the microflora is minimal. It shouldn’t be used by children younger than 12 and is not recommended during pregnancy or breastfeeding.

How To Avoid Traveler’s Diarrhea?

Always follow essential food safety and water safety advice while traveling.

Avoid raw meat and seafood. Consume only fresh and steaming hot meals and avoid food that’s been at room temperature for a long time (buffets, condiments). Avoid uncooked vegetables.

Always use safe bottled or purified water for drinking and washing fruit. Avoid ice in countries with unsafe tap water.

Advice about food safety often doesn’t reduce the likelihood of getting traveler’s diarrhea. This is usually because travelers can’t follow all the rules while enjoying and exploring a new destination and its cuisine. They might be on a budget or in places with insufficient food options, and the sanitation overall is bad.

Although it’s hard to avoid the infection when it’s on every corner, risk avoidance may still help reduce the risk of contracting serious infections such as helminths and other parasites.

Antibiotics and OTC Drugs for Prevention

Generally, antibiotic prophylaxis (prevention) of Traveler’s diarrhea is not recommended. This is because the on-demand use of antibiotics in combination with loperamide can, in many cases, shorten the duration of problems to less than a day. However, there are all sorts of risks in using antibiotics.

Antibiotic prophylaxis can be recommended to people at high risk of health-related complications after getting sick, such as immunocompromised patients, people with type I diabetes, kidney failure, IBD, AIDS, etc.

For these and others, if prophylaxis is indicated, rifaximin is recommended.

Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto Bismol®, Pepti-Calm®) may be considered for any traveler to prevent traveler’s diarrhea.

It reduces the risk of getting sick by 65% when given four times a day. The dosages studied were 2.1 g/day or 4.2 g/day for a maximum of four weeks. It’s up to the traveler and their physician to decide if prophylaxis is desired, keeping the side effects in mind.

The combination of bismuth salicylate and doxycycline (malarial prophylaxis) should be avoided.

Do Probiotics Work to Prevent and Treat Traveler’s Diarrhea?

Probiotics are currently not recommended for preventing or treating traveler‘s diarrhea simply because of a lack of data.

Few studies were conducted on using probiotics for this purpose, and the results weren‘t convincing enough. The studies used different doses of different types of probiotics and tested them in limited areas, making it hard to assess their effectiveness.

More work has to be done to address this issue. Probiotics are regularly used to treat post-antibiotic diarrhea in patients using antibiotics after abdominal surgeries, and they look promising for use in many other health issues.

From the data available on preventing traveler’s diarrhea, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and boulardii showed some potential effect, but they were tested in a small region.

Is There a Vaccine for Traveler’s Diarrhea?

Creating a single vaccine is impossible because many pathogens are responsible for traveler’s diarrhea.

The Cholera vaccine provides limited cross-protection against one subtype of E. coli—ETEC (against the toxin produced by it, to be exact)—responsible for most cases of traveler’s diarrhea. However, the overall efficacy is only around 7% or less. Therefore, it’s advised to use this vaccine only for its primary purpose.

There are a couple of vaccines targeting ETEC in different stages of clinical trials. The main reason for development is not traveling but the children in developing countries who are at risk of death from dehydration when getting diarrhea.

Diarrhea is the third leading cause of death in children under the age of 5, according to WHO. That is 444,000 children a year. ETEC is often responsible for this.

ETVAX® is the only vaccine in late-stage clinical trials showing a great safety profile in children and the travelers population. There is some promising news from Gambia, where the oral vaccine is tested to drastically reduce the death rate in one of the hospitals year over year, but we’ll have to wait for the final results.

There is also a vaccine candidate against Norovirus currently in trials.

Both vaccines might be available to travelers in a few years.

What to Pack: Essential Items for Traveler’s Diarrhea

Don’t count on foreign pharmacies, as these medicines might not be available or approved. Counterfeit drugs can also be found in many low-income countries.

Pack Loperamide and bismuth subsalicylate. Add ORS packs if traveling with children. Consult your physician about prescribing antibiotics. Make sure to pack hand sanitizer. If you don’t want to be dependent on bottled water, bring the water purifier of your choice.

Easy-to-Follow Algorithm for Traveler’s Diarrhea

This was an extensive overview of Traveler’s diarrhea, as many of you will have to count on yourself while traveling in remote areas with limited medical help. For others, use this TLDR.

Step 0: consult your doctor about the antibiotic recommendation pre-travel

Step 1: self-determine the severity of diarrhea

Step 2: ensure hydration with safe liquids

Step 3:

- for mild diarrhea, use loperamide or bismuth subsalicylate

- for moderate diarrhea, use loperamide alone or with antibiotics

- for severe diarrhea, use antibiotics in combination with loperamide. Don’t use loperamide if fever and bloody stool is present. In this case, use antibiotics and seek medical attention

Step 4: Visit a physician if you feel worse after 48 hours of antibiotic treatment or if the symptoms persist for more than 14 days

Was this article helpful? Make sure to share it with your travel mates.

Subscribe to our newsletter so you don’t miss other essential health advice for travelers.

Resources

Tribble, D. R., Sanders, J. W., Pang, L. W., Mason, C., Pitarangsi, C., Baqar, S., Armstrong, A., Hshieh, P., Fox, A., Maley, E. A., Lebron, C., Faix, D. J., Lawler, J. V., Nayak, G., Lewis, M., Bodhidatta, L., & Scott, D. A. (2007). Traveler’s diarrhea in Thailand: randomized, double-blind trial comparing single-dose and 3-day azithromycin-based regimens with a 3-day levofloxacin regimen. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 44(3), 338–346. https://doi.org/10.1086/510589

DuPont H. L. (2007). Therapy for and prevention of traveler’s diarrhea. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 45 Suppl 1, S78–S84. https://doi.org/10.1086/518155

Angst, F., & Steffen, R. (1997). Update on the epidemiology of traveler’s diarrhea in East Africa. Journal of travel medicine, 4(3), 118-120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1708-8305.1997.tb00797.x

Fernandes, H. V. J., Houle, S. K. D., Johal, A., & Riddle, M. S. (2019). Travelers’ diarrhea: Clinical practice guidelines for pharmacists. Canadian pharmacists journal : CPJ = Revue des pharmaciens du Canada : RPC, 152(4), 241–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/1715163519853308

Riddle, M. S., Connor, B. A., Beeching, N. J., DuPont, H. L., Hamer, D. H., Kozarsky, P., Libman, M., Steffen, R., Taylor, D., Tribble, D. R., Vila, J., Zanger, P., & Ericsson, C. D. (2017). Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of travelers’ diarrhea: a graded expert panel report. Journal of travel medicine, 24(suppl_1), S57–S74. https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/tax026

Herbert L. Dupont, Traveling Internationally: Avoiding and Treating Travelers’ Diarrhea, Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Volume 8, Issue 6, 2010, Pages 490-493, ISSN 1542-3565, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2009.11.015.

von Sonnenburg, F., Tornieporth, N., Waiyaki, P., Lowe, B., Peruski, L. F., Jr, DuPont, H. L., Mathewson, J. J., & Steffen, R. (2000). Risk and aetiology of diarrhoea at various tourist destinations. Lancet (London, England), 356(9224), 133–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02451-X

Taylor, D. N., Bourgeois, A. L., Ericsson, C. D., Steffen, R., Jiang, Z. D., Halpern, J., Haake, R., & Dupont, H. L. (2006). A randomized, double-blind, multicenter study of rifaximin compared with placebo and with ciprofloxacin in the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 74(6), 1060–1066.

Barrett J, Brown M. Travellers’ diarrhoea BMJ 2016; 353. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1937

Ericsson, C. D., DuPont, H. L., Okhuysen, P. C., Jiang, Z. D., & DuPont, M. W. (2007). Loperamide plus azithromycin more effectively treats travelers’ diarrhea in Mexico than azithromycin alone. Journal of travel medicine, 14(5), 312–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1708-8305.2007.00144.x

DuPont, H. L., Ericsson, C. D., Farthing, M. J., Gorbach, S., Pickering, L. K., Rombo, L., Steffen, R., & Weinke, T. (2009). Expert review of the evidence base for prevention of travelers’ diarrhea. Journal of travel medicine, 16(3), 149–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1708-8305.2008.00299.x

Steffen, R. (2005). Epidemiology of traveler’s diarrhea. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 41(Supplement_8), S536-S540.

Seif S Al-Abri, Nick J Beeching, Fred J Nye, Traveller’s diarrhoea, The Lancet Infectious Diseases, Volume 5, Issue 6, 2005, Pages 349-360, ISSN 1473-3099, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70139-0.

Pitz, A. M., Park, G. W., Lee, D., Boissy, Y. L., & Vinjé, J. (2015). Antimicrobial activity of bismuth subsalicylate on Clostridium difficile, Escherichia coli O157:H7, norovirus, and other common enteric pathogens. Gut microbes, 6(2), 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2015.1008336

Leung, A. K. C., Leung, A. A. M., Wong, A. H. C., & Hon, K. L. (2019). Travelers’ Diarrhea: A Clinical Review. Recent patents on inflammation & allergy drug discovery, 13(1), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.2174/1872213X13666190514105054

Basmah F. Alharbi, Abeer A. Alateek, Investigating the influence of probiotics in preventing Traveler’s diarrhea: Meta-analysis based systematic review, Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, Volume 59, 2024, 102703, ISSN 1477-8939, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2024.102703.

Lynne V. McFarland, Meta-analysis of probiotics for the prevention of traveler’s diarrhea, Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, Volume 5, Issue 2, 2007, Pages 97-105, ISSN 1477-8939, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2005.10.003.

Ibrahim Khalil, John D. Anderson, Karoun H. Bagamian, Shahida Baqar, Birgitte Giersing, William P. Hausdorff, Caroline Marshall, Chad K. Porter, Richard I. Walker, A. Louis Bourgeois, Vaccine value profile for enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC), Vaccine, Volume 41, Supplement 2, 2023, Pages S95-S113, ISSN 0264-410X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.02.011.

Paulke-Korinek, M., Kollaritsch, H. (2014). Treatment of Traveler’s Diarrhea. Current Treatment Options in Infectious Diseases (6), 74–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40506-013-0002-0

Hoy, S.M. Rifamycin SV MMX®: A Review in the Treatment of Traveller’s Diarrhoea. Clin Drug Investig 39, 691–697 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40261-019-00808-2

McFarland, L. V., & Goh, S. (2019). Are probiotics and prebiotics effective in the prevention of travellers’ diarrhea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel medicine and infectious disease, 27, 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2018.09.007

The Lancet Infectious Diseases, Volume 20, Issue 2, 2020, Pages 208-219, ISSN 1473-3099, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30571-7.

https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB00836

Map: Created with MapChart: https://www.mapchart.net/index.html

Data from Steffen r, Hill Dr, DuPont Hl. Traveler’s diarrhea: a clinical review. JaMa 2015; 313: 71-80

Disclaimer:

The information provided in this blog post is for general informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any health problem. The use or reliance on any information provided in this blog post is solely at your own risk.