Rabies is one of the deadliest infectious diseases of all. Once the symptoms arise, the probability of death is close to 100%. It doesn’t matter if you’re in the best hospital in the world. There’s just nothing to do about it.

If you got to this article from googling Rabies symptoms, thinking you might have it, this probably scared you (to put it mildly).

Rabies is extremely rare in developed countries. So rare, that most physicians would probably google “Rabies symptoms” as well because the last time they heard about it was in medical school. This disease is still quite common in Asia and Africa, even in tourist spots like Thailand or Indonesia.

It’s very hard to say if the animal contracts the virus (in many cases, the chance is extremely low). In combination with an almost 100% chance of death, if the treatment is not started soon, we get to a very difficult position, especially in travelers.

So, let’s dive in!

In This Article

What is Rabies?

Rabies is a viral disease with different variants that circulate in animals. It can infect any warm-blooded host, but it’s seen mostly in dogs, bats, and other wildlife.

The virus is kept under control by mass vaccination of dogs in developed countries.

It’s estimated that 14,000 to 59,000 people worldwide die every year because of the disease, with approximately 40% of them being children under 15. Most of them in Asia and Africa.

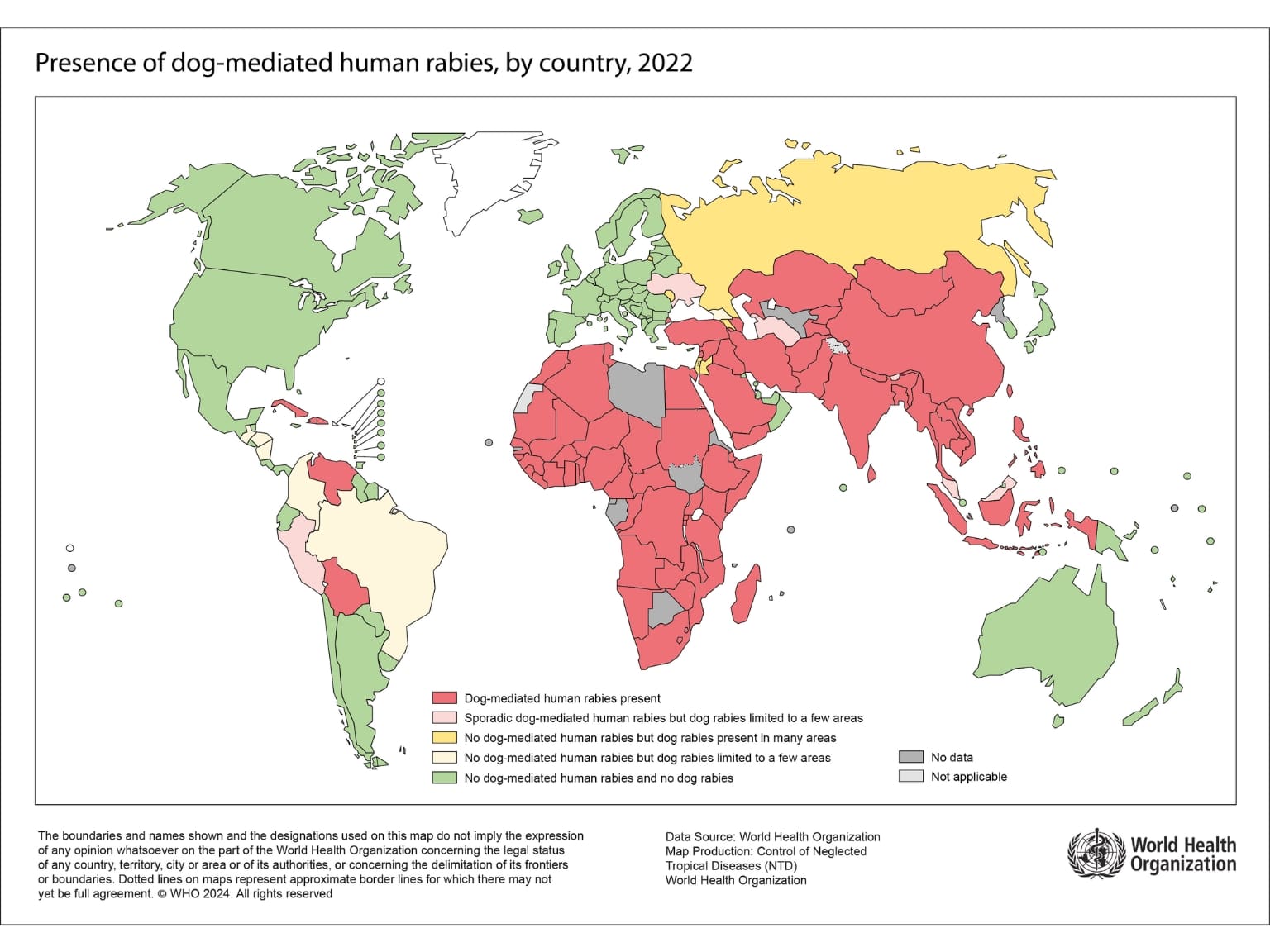

In which countries are Rabies most common?

The majority of cases occur in Asia. India is the most affected country by far, with approximately 20,000 deaths per year.

Less than half of deaths occur in Africa, where a large population of stray dogs and limited resources for dog vaccination and prevention for people contribute to the risk.

The number of cases, along with the risk level, is generally very low in Latin America. The map below shows where dog-mediated Rabies is present.

How is Rabies transmitted?

The rabies virus is transmitted when saliva from an infected animal comes into contact with a person’s wound or mucous membrane (mouth, nose, eyelids, etc.).

This typically happens through an animal bite or a scratch, but it can also happen more subtly, like a dog licking broken or injured skin.

After the bite, the virus tries to infect the peripheral nerve. From there, it spreads to the central nervous system, attacking the brain. Then, it multiplies more in other peripheral nerves, including salivary glands, and appears in saliva.

Because of this route, the risk of getting infected is higher when the saliva gets to body parts with many nerves (hands, face). Bites and scratches closer to the brain will probably shorten the duration of the incubation period.

How risky was the contact with an animal?

The WHO recognizes three categories of contact. These might be helpful to you in self-assessment.

For Category II and III, you should immediately seek medical help, and the physicians should start the treatment.

Category I – touching or feeding animals, animal licks on intact skin (no exposure)

Category II – nibbling of uncovered skin, minor scratches or abrasions without bleeding (exposure)

Category III – single or multiple transdermal bites or scratches, contamination of mucous membrane or broken skin with saliva from animal licks, exposures due to direct contact with bats (severe exposure)

High-risk animals for Travelers:

Dogs:

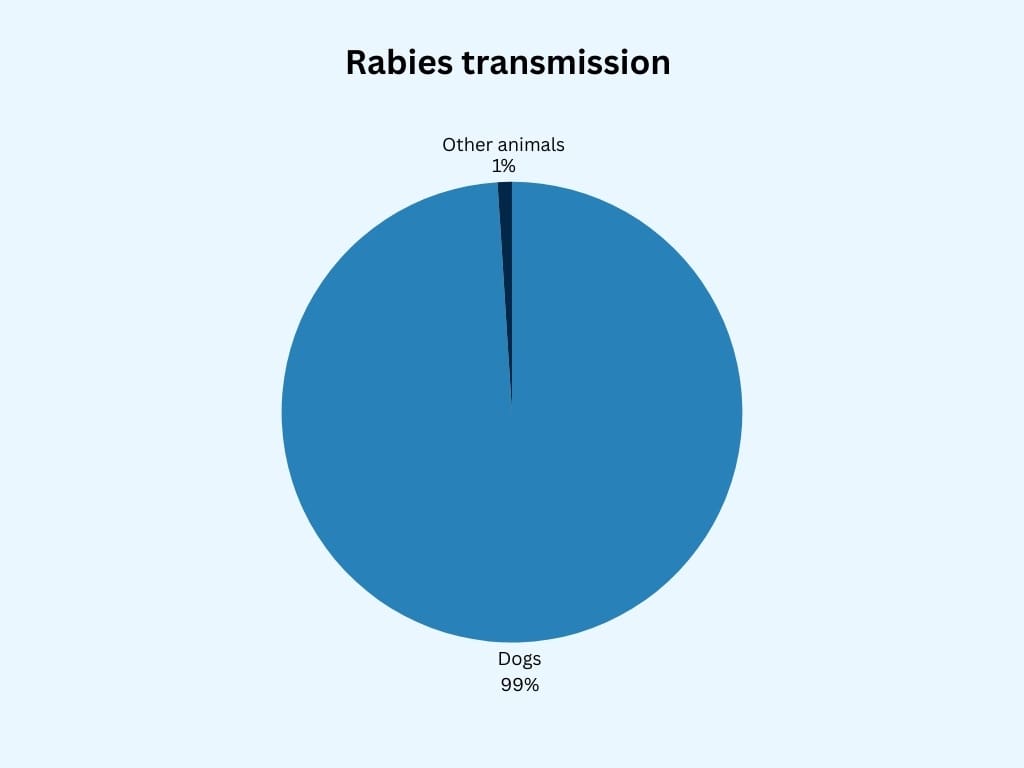

Dogs are responsible for 99% of the Rabies transmission. They are the main reservoir in low and middle-income countries.

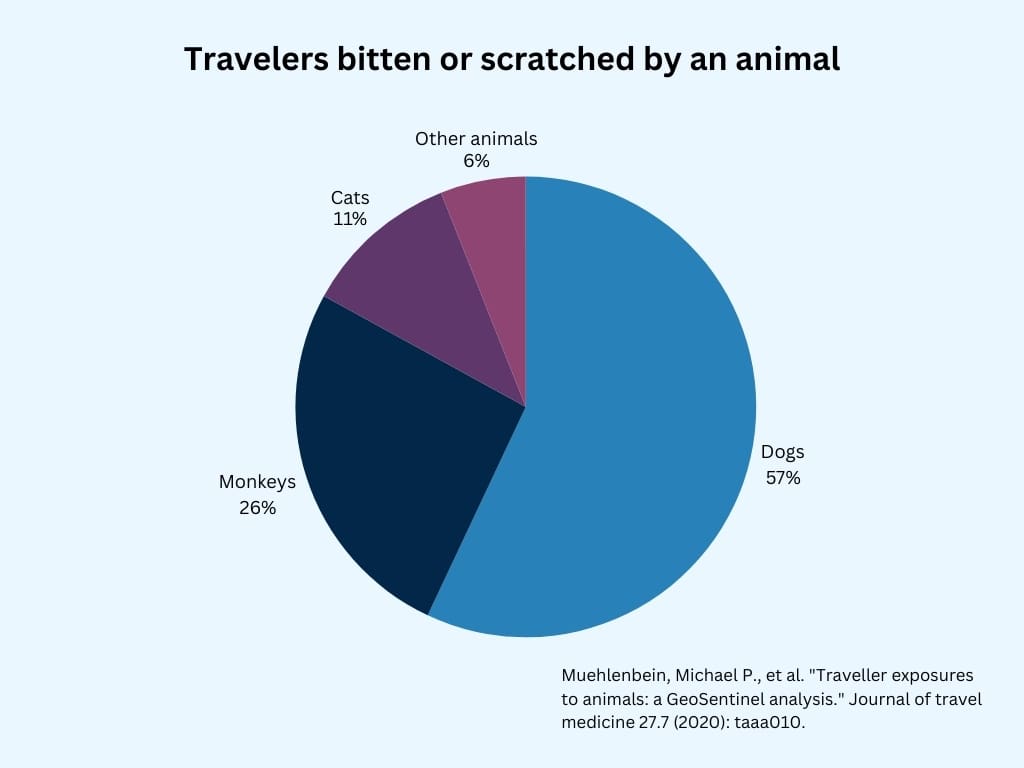

There is a large population of stray dogs in many countries. These dogs can be aggressive in groups, but unprovoked attacks are not that frequent. Often, dogs are approached, petted, or fed by travelers, especially children.

Research found that travelers bitten by a dog once are almost never bitten a second time. This, along with other data, suggests that awareness and caution in situations when dogs are around can very effectively prevent a dog bite.

Bats:

Contact with bats is much less common than with dogs. However, if contact occurs, the risk of an infection is very high.

A bite or other exposure to a bat is an indication to immediately seek medical attention and act fast. This applies even in countries where no case of rabies has been confirmed in years.

If you come in contact with a bat, thoroughly scan the skin, as their teeth are very small, and the wound might not be visible.

Primates:

Monkeys and other primates are rarely rabid. However, bites and scratches are quite common among travelers as these animals are often in tourist places.

They are accustomed to close contact with people, and many travelers try to feed or pet them to get a cute photo. In several studies, Monkeys were responsible for most of the injuries in travelers seeking medical help in Southeast Asia, many of them in Bali.

Although the risk of infection is much lower than in dogs, we get back to the 100% mortality problem.

Local physicians will probably recommend treatment to avoid „dead rabid tourist“ titles in the newspaper. Jokes aside, I’d do the same and follow the guidelines.

Cats and wildlife:

Any bite, scratch, or other exposure to the saliva of a warm-blooded animal must be assessed individually by a local specialist.

In 2011, there was a Rabid Zebra incident in Kenya. The Zebra was bitten by a dog suspected of being rabid. They didn’t catch the dog to test it. Meanwhile, the visitors kept petting and feeding the zebra until it fell ill, died, and was diagnosed with Rabies. There were 243 travelers from 17 countries at risk of infection; luckily, none of them died.

Rabies symptoms in humans

After infection, the incubation period varies significantly but typically lasts 1 to 3 months.

The first symptoms are often pain or numbness at the bite site, followed by fever and malaise.

Neurological symptoms are anxiety, paralysis, and fear of water, triggering swallowing muscle spasms.

When the history of animal contact is unknown, it can be mistaken for pharyngitis (sore throat) in the early stage.

The virus continues to attack brain tissue, causing encephalitis. It progresses to delirium, seizures, coma, and eventually death from respiratory or cardiac failure, often within a week after onset of symptoms.

What to do if bitten by an animal abroad?

- Wound care:

Wash the wound thoroughly with soap and water for at least 15 minutes. If available, apply iodine disinfection or another virucidal agent. This step, done correctly, significantly reduces the risk of infection. - Seek medical Care:

Head to the hospital as soon as possible. Keep in mind this has to be a hospital with rabies vaccination and potentially rabies immunoglobulin available. The administration should be performed as soon as possible, ideally on the same day.

Post-exposure rabies treatment (prophylaxis)

I may have used the word treatment before, but the truth is there is no treatment to stop the disease from killing the host.

The only way to “treat it” is to prevent the virus from replicating in the peripheral nerves. Once the virus enters the nerve, the immune system can’t stop it.

The long incubation period allows the vaccine to be administered and lets the immune system produce antibodies to stop the virus from entering the nerve. If this is performed fast enough, the virus is stopped before it’s too late.

Rabies antibodies are sometimes used for immediate protection.

Postexposition prophylaxis:

Also known as PEP, it should be started for all contacts with potentially rabid animals in categories II and III mentioned earlier.

Unvaccinated patients:

Protocols can slightly differ, but in general, four doses of Rabies vaccine are recommended (day 0, 3, 7, 14).

For severe exposure, the application of Rabies immunoglobulin (pre-formed antibodies) is recommended.

This should be administered ideally on day 0, but if it’s not available up to 7 days after the first dose of vaccine.

Vaccinated patients:

Those who received a full course of vaccination, either preventively or as part of PEP in the past, must receive two doses of the vaccine.

After the application on day 0 and day 3, a swift immune response is expected, even if the last vaccination was many years before.

Immunoglobulin is not recommended.

Besides the high cost of immunoglobulin and the need for four hospital visits, there are more issues unvaccinated travelers should be aware of.

Rabies vaccine abroad

Besides modern CCV (cell-culture vaccines) like Verorab and Rabipur, older DEV (duck embryo vaccines) are widely used in developing countries because of their cost.

These vaccines are banned in the US, Europe, and other countries because of potential severe side effects.

Vaccinated travelers are advised to delay the treatment for up to 1 day to receive CCV rather than DEV. Unvaccinated travelers don’t have this luxury, as the speed of receiving the vaccine is more important.

Rabies immunoglobulin abroad:

The immunoglobulin also comes in two forms. Derived from human and horse blood.

Human rabies immunoglobulin (HRIg) is preferred but can be expensive and unavailable, especially outside of bigger cities. Lack of immunoglobulin in many countries results in local healthcare providers not following the recommendations.

Available studies show that just 4% to 25% of international travelers are given Rabies immunoglobulin when indicated.

Medical evacuation insurance is a good idea in high-risk areas where proper medical attention is inaccessible.

Correctly administering the PEP according to the recommendations has practically a 100% chance of success.

Also, there isn’t any case of death recorded of previously vaccinated people given booster after exposure to rabid animals.

Rabies vaccination for travel

Recently, the WHO proposed changing the 3-dose vaccination schedule to just a 2-dose course, with the second dose after 7 days. Many countries, including the US, have adopted this.

In some travelers with sustained high risk, the third dose might be recommended within 3 years.

Long-lasting immunity and the ability of the immune system to produce antibodies quickly after the booster is given were proven in many studies.

Therefore, regular preventive boosters are not required for travelers and are reserved for special groups of people, such as lab workers and animal caregivers.

The price of the Rabies vaccine in the US ranges between $350 and $500 per dose.

Should I get a Rabies shot?

The risk assessment and vaccine recommendation is very complex.

The main risk factors include:

- Destination:

South-East Asia, India, and Northern Africa have the highest rates of dog-mediated Rabies. - Remoteness and Health care quality:

Traveling to places where the nearest hospital is far away or where immunoglobulin and modern vaccines are unavailable.

You can check the availability of these in each country on this CDC website - Activities:

Outdoor activities, close contact with animals - Age:

Children have a higher risk of getting bitten or scratched by a dog as they often can’t evaluate the risk, are more likely to approach animals, and might not report minor injuries to adults.

Cumulative exposure might be a factor in deciding. Frequent travelers at occasional risk could benefit from the long-lasting effect of the vaccination, and investing in the vaccine early could be time-saving, cost-saving, and life-saving in the future.

Preventing Rabies exposure

0,4% of travelers will get bitten by an animal per month in countries where Rabies is a potential risk.

The best prevention of all is avoiding bites.

In a German study, more than half of the injured travelers approached the animals before the attack.

Avoid petting, feeding, or playing with dogs or monkeys, especially if you have broken exposed skin.

Avoid handling bats and other wildlife. Consider using respiratory protection before entering the cave where bats live.

Rabies may be one of the deadliest diseases, but it is also one of the most preventable.

By understanding the risks, avoiding animal contact, and considering pre-travel vaccination, you can protect yourself against this fatal disease.

Resources

Bantjes, S. E., Ruijs, W. L., van den Hoogen, G. A. L., Croughs, M., Pijtak-Radersma, A. H., Sonder, G. J., … & Haverkate, M. R. (2022). Predictors of possible exposure to rabies in travellers: A case-control study. Travel medicine and infectious disease, 47, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102316

Travel Medicine, 4th Edition – December 13, 2018, Authors: Jay S. Keystone, Phyllis E. Kozarsky, Bradley A. Connor, Hans D. Nothdurft, Marc Mendelson, Karin Leder, Language: English, Hardback ISBN: 9780323546966

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023). CDC Yellow Book 2024: Health Information for International Travel. Oxford University Press.

Saffar, F., Heinemann, M., Heitkamp, C., Stelzl, D. R., Ramharter, M., Schunk, M., … & Bühler, S. (2023). Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis of international travellers-results from two major German travel clinics. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, 53, 102573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2023.102573

Gautret, P., & Parola, P. (2014). Rabies in travelers. Current infectious disease reports, 16(3), 394. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11908-014-0394-0

Gautret, P., & Parola, P. (2012). Rabies vaccination for international travelers. Vaccine, 30(2), 126-133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.007

Shlim, D. R. (2018). Preventing rabies: the new WHO recommendations and their impact on travel medicine practice. Journal of Travel Medicine, 25(1), tay119. https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/tay119

Lankau, E. W., Montgomery, J. M., Tack, D. M., Obonyo, M., Kadivane, S., Blanton, J. D., … & Rupprecht, C. E. (2012). Exposure of US travelers to rabid zebra, Kenya, 2011. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 18(7), 1202.

Rabies vaccines and immunoglobulins: WHO position April 2018 https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/immunization/position_paper_documents/rabies/pp-rabies-summary-2018.pdf?sfvrsn=c9d92ce5_2#:~:text=The%20WHO%20rabies%20exposure%20categories,contamination%20of%20mucous%20membrane%20or

Disclaimer:

The information provided in this blog post is for general informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any health problem. The use or reliance on any information provided in this blog post is solely at your own risk.