The ocean’s beauty comes with hidden risks. I’m not talking about sharks, which cause dramatically fewer injuries than other marine animals (less than 100 attacks per year).

Frequent injuries range from jellyfish, spiny starfish, and sea urchin stings to contact with fire corals. Stingray and venomous fish encounters are rare but dangerous.

This guide explores therapies for injuries caused by various marine creatures, ensuring you are prepared for your underwater adventures. Understanding the risks and how to respond can save lives and prevent complications. Let’s dive in!

In This Article

This post includes affiliate links. If you choose to purchase through these links, I may receive a commission, helping me continue creating valuable content for you. This comes at no additional cost to you.

Jellyfish Stings: Floating Hazards

Jellyfish are among the oldest living organisms on this planet. Though there are many fascinating things about these creatures, like Box jellyfish having 24 eyes with a 360-degree view or some species living only a few minutes while others are possibly immortal, we will focus on their ability to sting.

When the tentacle makes contact with our skin, millions of specialized cells inject venom into the body. Some species do not harm, some will cause skin irritation or pain, and just a small fraction of species are able to severely injure or kill a human.

Deadly Australian box jellyfish can cause death in seconds due to the systemic effect of poison. One can lose consciousness in minutes, which poses a risk of drowning and, later, low blood pressure, cardiac arrest, or inability to breathe due to paralysis. This scenario happens in 15% to 20% of cases and is highly dependent on the affected area and availability of antivenin.

If you want to avoid these creatures, they appear along the Australian north coast and tropical waters of the Indo-Pacific between October and June. Coast areas often monitor these, so watch out for any warnings.

Another dangerous jellyfish is the Portuguese man of war, which is found in the tropical and subtropical parts of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

Stings are rarely deadly but often extremely painful. Systemic reactions like fever, shortness of breath, and cardiac distress may occur after exposure to a large number of tentacles. As they can’t actively move, they can often be found ashore after high tide or strong wind.

Treatment:

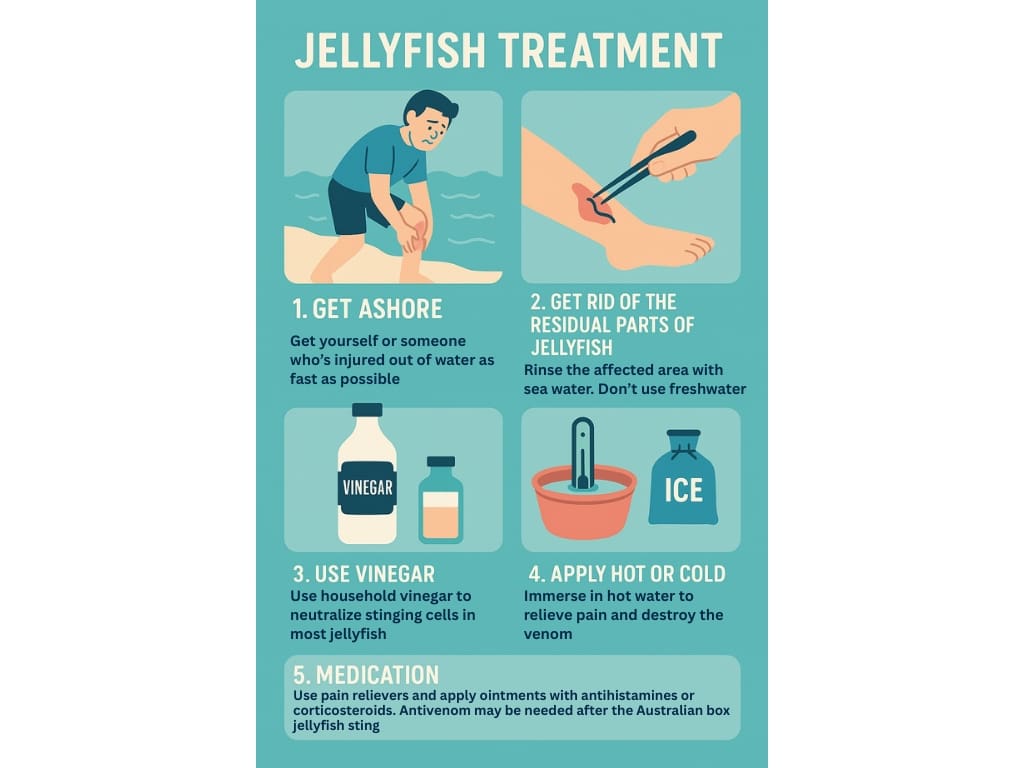

- Get ashore

Get yourself or someone who’s injured out of water as fast as possible while remaining calm. Panic, pain, and the effect of venom can cause muscle spasms, which can lead to drowning. In severe cases of box jellyfish stings, it’s important to call for help, call an ambulance, and start with first aid, which can include CPR. - Get rid of the residual parts of jellyfish

Remove the tentacles without directly touching them. The cells containing poison stay on the skin after the jellyfish is removed. Rinse the affected area with seawater, even if there are no visible parts. Never use fresh water! It has a lower concentration than seawater, and it’ll make the cells pop, releasing even more venom. The same applies to urine. - Use vinegar

There are dozens of folk remedies, including urine or alcohol, that are controversial. For most jellyfish species, 5% acetic acid (household vinegar) is effective in neutralizing the stinging cells. It’s advised after all stings in tropical areas, mainly because of the box jellyfish.

Vinegar is not generally advised in waters of the Atlantic (US east coast, Mexico) or anytime the Portuguese Man O’ War is identified. In this jellyfish, vinegar can trigger the release of poison. Therefore, only seawater is used in this case. - Apply hot or cold

For most jellyfish, immersing the stung area in hot water (40–45°C or 104–113°F) will relieve the pain and help destroy the remaining venom. However, cold compression is advised for some tropical species, especially Australian box jellyfish. - Medication

Antivenom application may be necessary after the Australian box jellyfish sting. If a large area is affected, opioids might be used in the first hours. OTC painkillers, such as acetaminophen, ibuprofen, etc., may be used for pain relief in most stings.

Antihistamines and local ointments with steroids may help with local reactions. It can take a few days to stop the itchiness and pain. Changes in pigmentation or texture of the skin can persist for months.

Venomous Fish: Painful Encounters

Most fish are harmless, and they’ll keep their distance from humans. They typically cause injury to feet and legs after unknowingly stepping on them. Fishermen can be injured while handling these animals.

Stonefish:

The name is self-explanatory after seeing this species. It can be found in shallow waters around coral reefs in tropical parts of the western Pacific Ocean and Indian Ocean (mostly South East Asia, Australia) and in coastal areas of East Africa.

It is the most venomous fish, using venomous spines to hunt its prey. Unfortunately, its tactics include camouflage while waiting for the strike, which means it’s hard to spot.

The sting causes extreme pain and swelling, and the wound healing can take months. If enough venom is injected, symptoms like abdominal pain, vomiting, heartbeat irregularities, heart failure, and seizures can occur.

Lionfish:

Lionfish are found in most tropical waters around the world. They can use their spines to defend against humans, resulting in painful wounds. Headache, vomiting, and difficulty breathing sometimes occur, but death is very rare.

Stingray:

These pancake-shaped sea rays are common in tropical and subtropical marine waters around the world. They’re not aggressive, and when threatened, they tend to swim away rather than use their tail spine. When they do, it’s after unintentionally stepping on them, and most injuries are to feet, as the tail can sting you over the stingray’s body, typically when the animal is on the bottom of the sea.

The sting is very painful, causing deep wounds, sometimes nausea, muscle cramps, headache, or fever. The venom is not dangerous.

Severe injuries are rare and always caused by the spine penetrating vital organs, not by toxicity of the venom. This includes an unfortunate incident leading to the death of great Australian conservationist Steve Irwin; his chest was penetrated by a stingray, fatally injuring the heart.

Treatment:

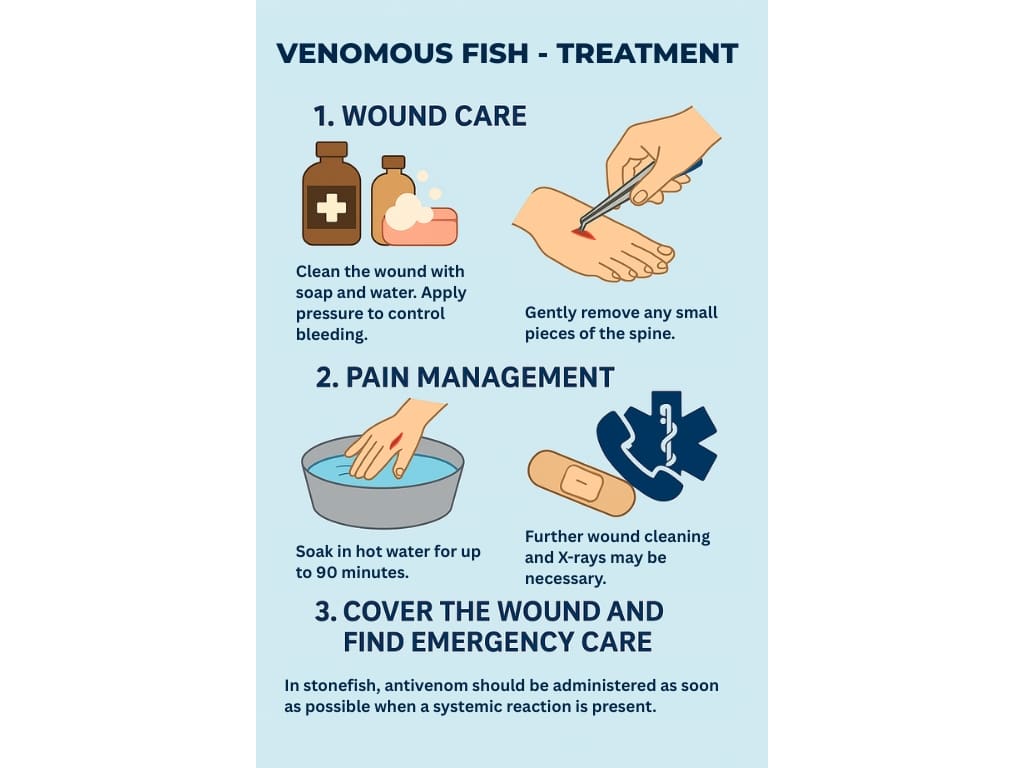

- Wound Care

Clean the wound thoroughly with soap and water to remove debris. Apply pressure to the wound to control bleeding. Gently remove any small pieces of the spine. Do not remove barbs and stingers embedded in the chest, neck, or abdomen, and seek emergency care. Also, seek medical help immediately after a stonefish sting. - Pain Management

Soak the injured body part in hot water (110 – 115°F/ 42 – 45°C) for up to 90 minutes. This helps with pain relief and is thought to deactivate the venom in some cases. - Cover the wound and find emergency care

Further wound cleaning and X-rays to search for fragments may be used. The staff might prescribe antibiotics to prevent wound infection and pain killers. In stonefish, antivenom should be administered as soon as possible when a systemic reaction is present. Medical evacuation to the nearest hospital with antivenom might be needed.

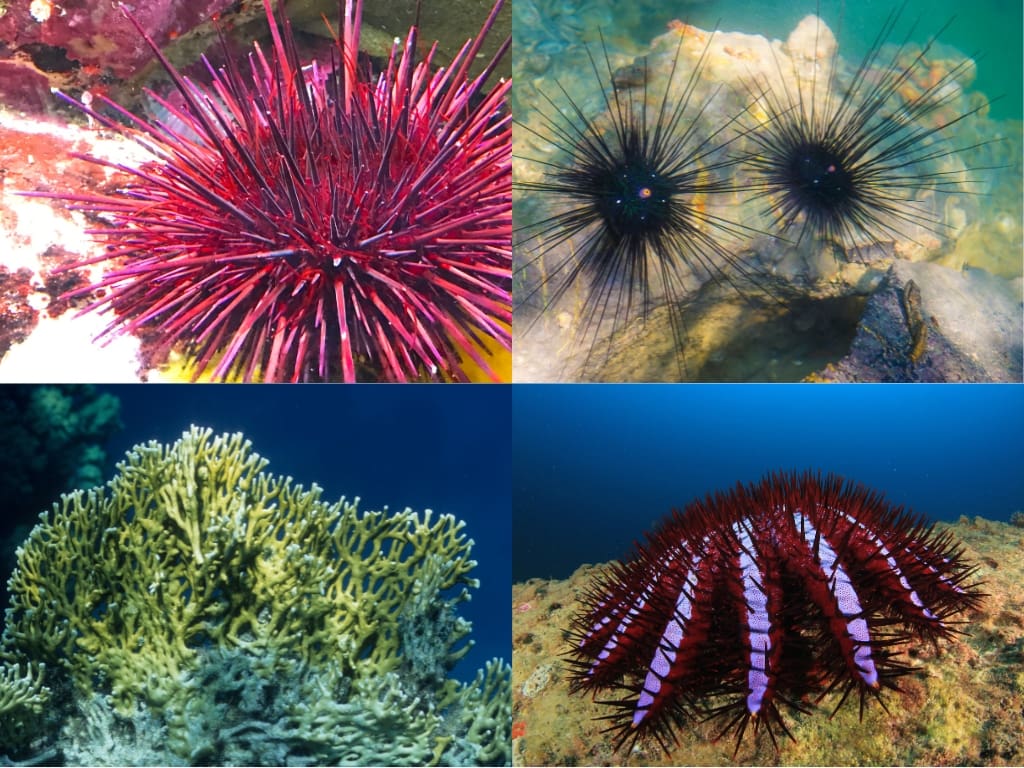

Sea Urchins, Star Fish, and Fire Coral: Passive Aggressive

These creatures cause minor injuries to many travelers without even moving.

Stepping on an urchin in shallow water or coming in contact with fire coral while snorkeling and diving results in pain, skin reaction, and risk of infection.

The crown-of-thorns starfish has long toxin-containing spines. Sting can result in pain, swelling, nausea, muscle paralysis, or coagulopathies. They can be found anywhere from the East African coast to the Pacific coast of Central America in tropical coral reefs.

Other starfish are not dangerous, but you shouldn’t touch or take them out of the water. This behavior can lead to suffocation, stress, bacterial contamination, or other harm to the starfish.

Contact with fire coral causes symptoms similar to most jellyfish, and the same treatment should be followed.

Treatment:

- Wound Care

Remove any small pieces of the spines in precisely reverse direction. They tend to break easily. Surgical removal is necessary if any fragments stay in the wound or the wound is not healing. Clean the wound thoroughly with soap and water. - Pain Management

Soak the injured body part in hot water (110 – 115°F/ 42 – 45°C) for 30 – 60 minutes, or longer if needed. Towels soaked in hot water may be used too. - Medication

Based on the severity, painkillers, antihistamines, and local steroid ointments may be recommended. A preventive course of antibiotics may be needed for large or deep injuries.

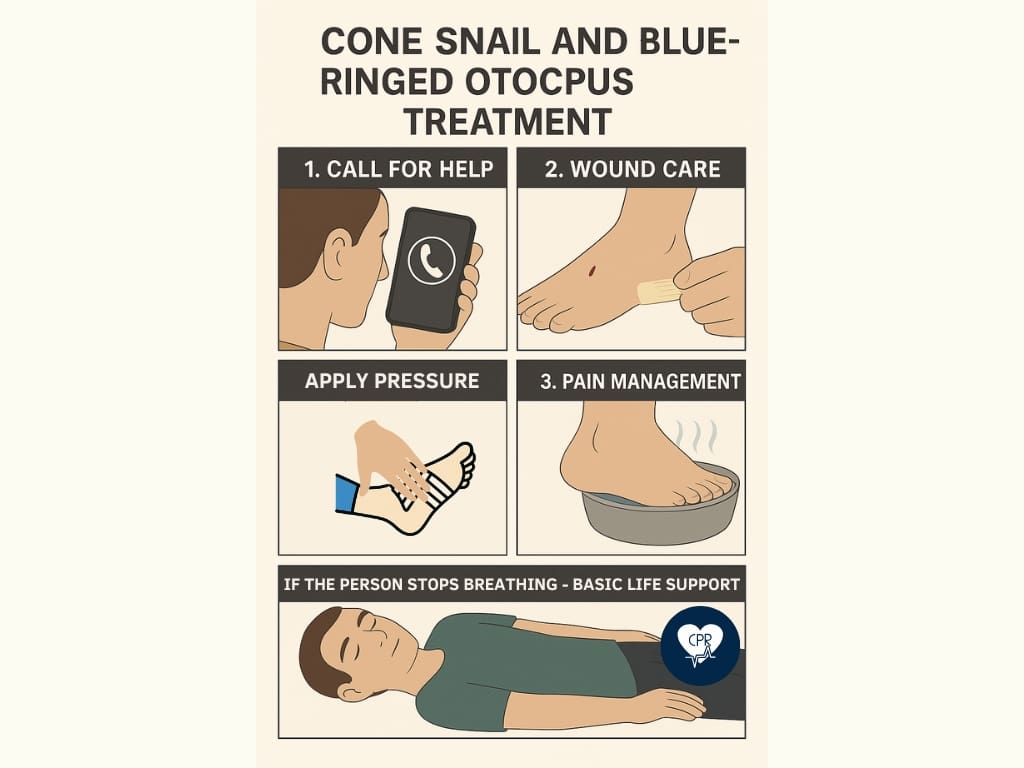

Cone Snails and Blue-Ringed Octopus: Tiny but Deadly

Exposure to these is extremely rare, but they both can and did kill a human. With their sting, they inject toxins that may lead to paralysis and respiratory death in a few hours.

All species of cone snails are venomous. The most dangerous one is the geography cone, hunting small fish firing its harpoon-like tooth. It’s found in tropical marine waters around reefs and in mangroves.

Treatment:

- Call for help

Call an ambulance or prepare for an evacuation to the nearest hospital. There is no specific treatment. Supportive therapy, including artificial ventilation, might be needed until the body gets rid of the toxins. - Wound Care

Clean the wound with soap and water to remove debris. Apply pressure immobilization bandage to the wound to slow down the toxins. - Pain Management

Soak the injured body part in hot water (110 – 115°F/ 42 – 45°C). This helps with pain relief but doesn’t affect the venom.

Start basic life support if the person stops breathing.

Prevention

- Wear protective swimsuits when diving or doing watersports in areas with jellyfish.

- Be aware of your surroundings when swimming. Don’t touch the jellyfish in the water or on the beach.

- Pay attention to local warnings about jellyfish activity.

- A sunscreen with jellyfish sting protection is available that should be effective against mild jellyfish stings.

- Wear protective footwear in shallow waters.

- Shuffle your feet while wading in shallow water to avoid stepping on stingrays.

- Wear water shoes to protect against sharp spines.

- Avoid handling venomous fish like stonefish or lionfish.

- Do not handle marine animals, including those that are not moving.

- Don’t pick up cone-shaped shells.

- Use caution while exploring tidal pools.

- Avoid touching coral reefs or stepping near sea urchins.

Marine infections

Infections are a common complication after injuries in marine environments. People with weakened immune systems or conditions like liver or kidney disease are at a higher risk of serious infections caused by bacteria such as Vibrio carchariae, Vibrio vulnificus, and Vibrio parahaemolyticus.

Keep fresh injuries and broken skin under a water-resistant bandage while swimming.

Symptoms like rapidly spreading redness and swelling, darkened skin, or blood-filled blisters should prompt immediate medical attention.

Oral or intravenous antibiotics and consultation with infection specialists and surgeons may be necessary.

Marine animal injuries can be avoided with the right precautions.

Wear protective gear, educate yourself about local marine life, and carry a well-equipped first-aid kit. Remember, swift and appropriate treatment can help relieve the pain, prevent complications, and save lives in severe cases.

Explore more tips on staying safe during your adventures in our other blog posts.

Don’t forget to share this guide with fellow ocean enthusiasts and ensure everyone is prepared for underwater adventures.

Resources

Travel Medicine, 4th Edition – December 13, 2018, Authors: Jay S. Keystone, Phyllis E. Kozarsky, Bradley A. Connor, Hans D. Nothdurft, Marc Mendelson, Karin Leder, Language: English, Hardback ISBN: 9780323546966

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023). CDC Yellow Book 2024: Health Information for International Travel. Oxford University Press.

Prentice, K. C., Himstead, A. S., Briggs, A. L., & Algaze-Gonzalez, I. M. (2023). Emergency Management Strategies and Antimicrobial Considerations for Nonmammalian Marine Vertebrate Penetrating Trauma in North America, the Caribbean, and Hawaii: A Review Article. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine, 34(1), 106-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wem.2022.09.008

Kropp, L. M., Parsley, C. B., & Burnett III, O. L. (2018). Millepora species (fire coral) sting: a case report and review of recommended management. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine, 29(4), 521-526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wem.2018.06.012

Lakkis, N. A., Maalouf, G. J., & Mahmassani, D. M. (2015). Jellyfish stings: a practical approach. Wilderness & environmental medicine, 26(3), 422-429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wem.2015.01.003

Boulware, D. R. (2006). A randomized, controlled field trial for the prevention of jellyfish stings with a topical sting inhibitor. Journal of travel medicine, 13(3), 166-171. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1708-8305.2006.00036.x

Kapil, S., Hendriksen, S., & Cooper, J. S. (2017). Cone snail toxicity. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470586/

Mark Lyon, R. (2004). Stonefish poisoning. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine, 15(4), 284-288. https://doi.org/10.1580/1080-6032(2004)015[0284:SP]2.0.CO;2

https://www.emergencyphysicians.org/article/know-when-to-go/jellyfish-and-stingray-stings

https://www.verywellhealth.com/how-to-treat-a-stingray-sting-1298267

https://oceanconservancy.org/blog/2024/01/12/caution-killer-cone-snails/

Some basic facts about marine species are from www.wikipedia.org

Disclaimer:

The information provided in this blog post is for general informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any health problem. The use or reliance on any information provided in this blog post is solely at your own risk.