Have you recently returned from an adventure abroad, only to find your stomach hasn’t settled down after two weeks?

Persistent diarrhea is present when the symptoms last 14 days or longer. It’s not as uncommon as you might think.

It’s seen in 3 to 10% of returned travelers. We talk about Chronic diarrhea after more than a month-long struggle, which occurs in 1 to 3% of travelers.

In contrast to acute traveler’s diarrhea, to which we dedicated another blog post, you should always seek medical attention.

The cause here is much more diverse and almost always requires some intervention. Ignoring the signs could mean missing a serious underlying issue.

In This Article

Let’s start with what’s NOT persistent diarrhea:

Diarrhea lasting more than 2 weeks but with a 5 to 7-day pause in between. In this case, it’s probably two distinct episodes of infectious acute diarrhea and should be treated as such.

The onset of vomiting or fever after ten days of diarrhea signals a second acute infection, as these symptoms usually occur at the beginning.

We can divide the causes of persistent diarrhea into three groups:

- Infectious

- Post-infectious

- Non-infectious

Infectious Causes of Persistent Diarrhea

Bacterial Infections

Bacteria common in traveler’s diarrhea, such as Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, or E. coli, rarely survive for more than two weeks, even without antibiotics.

The bacteria that play an important role here is Clostridium difficile. Diarrhea associated with this pathogen is common in hospitals after antibiotic treatment.

Simplified, this infection arises after broad-spectrum antibiotics kill the gut microflora. That’s when the bacteria has the right conditions to grow. And because the antibiotics recommended for treating traveler’s diarrhea are often the same type, it can result in unwanted side effects. This includes some antimalarials.

The possibility of bacterial infection is assessed depending on the antibiotics you’ve taken, the place you returned from, etc. Blood and stool samples might be checked.

Antibiotics such as metronidazole are used, often with probiotics. Advanced treatment, such as stool transplantation, is reserved for severe cases.

Parasitic Infections

Parasites are the most probable cause of infectious persistent diarrhea.

„In travelers to Nepal, for example, protozoans (parasites) were detected in 10% of patients whose symptoms lasted less than 14 days, as opposed to 27% of patients whose symptoms lasted more than 14 days.“

Giardia lamblia is the most common parasite found in returned travelers. Contaminated food or water with just 10 to 25 cysts (early-life form) can cause the infection.

The symptoms range from mild intestinal problems that resolve spontaneously to severe symptoms lasting weeks, such as fatigue, chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, and weight loss. Untreated, it may persist for months.

Other parasites include:

Entamoeba is acquired from contaminated food and water. In 90% of cases, it is asymptomatic.

The pathogenic variant, E. histolytica, is found in a 1:10 ratio to its harmless sibling. Rarely, it can migrate to the blood circulation, causing severe, potentially fatal problems.

Other less common parasites that enter the human body through the skin are Strongyloides and Schistosoma. They present various symptoms or survive without any symptoms for years or decades.

The life cycle of these creatures, along with the quality of the stool samples and the experiences of the person behind the microscope, might make it difficult to confirm the infection.

In some cases, rather than performing a duodenal biopsy, treatment for the Giardia infection might be prescribed without confirmation in a patient with good overall efficiency. Especially when upper gastrointestinal symptoms predominate – reflux, burping, discomfort.

STDs and Viral Infections

Some STDs, including HIV, can manifest with chronic diarrhea.

Men who have sex with men are at risk of giardiasis and other infections of the large intestine and rectum. This fact should be discussed with a doctor so that the diagnostics can be directed properly.

Tropical Sprue

Tropical sprue is a syndrome characterized by persistent diarrhea associated with a decreased ability to absorb proteins, fats, and some vitamins (B12 and folate). The unabsorbed fat causes specific slimy stool.

It affects long-term travelers and expatriates rather than short-term travelers.

The cause is infectious, but the exact pathogen is still unknown. The number of cases has declined rapidly in recent years, and the diagnosis is infrequent. It’s treated with antibiotics (tetracyclines).

Post-Infectious Causes

Post-Infectious Irritable Bowel Syndrome (PI-IBS)

Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort, diarrhea, bloating and other symptoms lasting for weeks after an episode of traveler’s diarrhea.

If other causes are ruled out, we talk about Post-Infectious Irritable Bowel Syndrome or PI-IBS.

It’s a result of injury to the outer layer of the intestine by bacteria. Although the infection might no longer be present after a few days, the damage is done. The inflammation persists, and the microbiome stays out of the balance.

It’s thought that the chances of developing PI-IBS after an acute episode of Traveler’s diarrhea is between 3% and 14%. The chances are higher with more severe infection (longer, worse symptoms).

The research on PI-IBS is one reason early self-treatment of traveler’s diarrhea is advised. Shortening the duration of illness should minimize the risk of this complication.

Various treatment options include elimination diets, high-fiber diets, the use of digestive enzymes, probiotics, and drugs targeting the main symptoms.

Poorly absorbed antibiotics such as Rifaximin can be effective, especially when bacterial overgrowth (imbalance in gut microflora) is present.

Temporary loss of digestive enzymes

Digestion, in a nutshell, is breaking down complex structures into basic compounds before transporting them from the gut to blood circulation. There are several steps, and the last one is breaking down disaccharides. Di—means two, and after breaking this, simple sugars will be ready to absorb.

Enzymes responsible for this are a part of a thin outer layer of the small intestine. After an acute inflammatory process, this layer is damaged and, in some cases, may take several weeks to renew. For this time, Lactose and Sucrose can’t be broken down, which means they can’t be absorbed and are left out for bacteria to feast on them.

Avoiding dairy products, sorbitol-containing products, fruit juices, concentrated sweets, and high-fat items is advised in this case.

Remember that this almost always happens after acute diarrhea but usually resolves after a few days. For these days, the same diet as described earlier should be followed.

Non-Infectious Causes

Celiac Disease

It’s a fact an acute infection is not a cause of Celiac disease, but it can often be a trigger.

Manifestation of Celiac disease can begin after an episode of traveler’s diarrhea in a genetically susceptible patient. This can start the manifestation of this condition.

Celiac disease can be present even without symptoms or only show laboratory clues for some time. Acute infection can unmask this condition.

Chronic diarrhea, weight loss, and blood tests should lead to confirming the diagnosis by biopsy with further monitoring and a strict gluten-free diet.

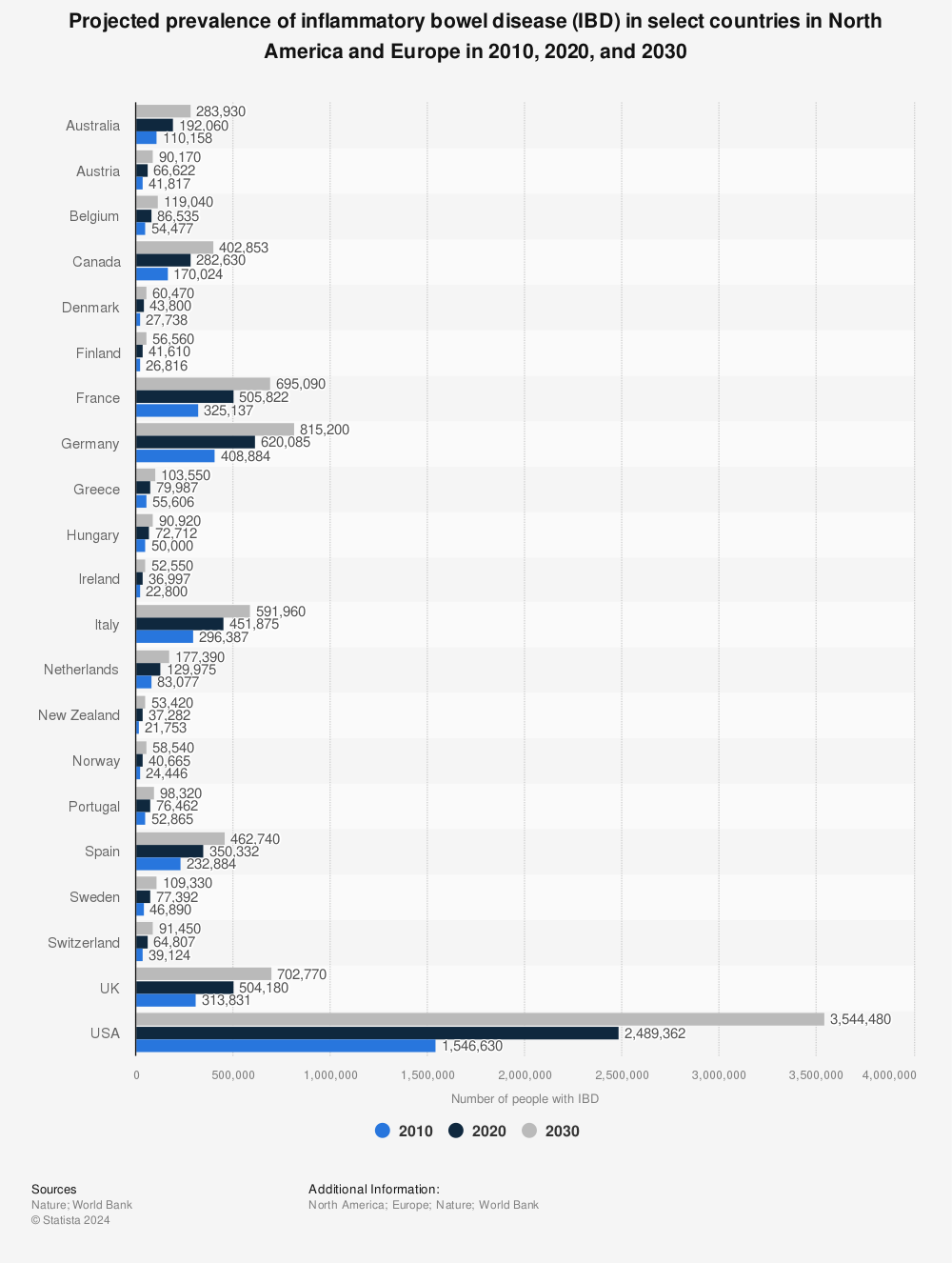

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

IBD cases are rapidly growing in recent years. The specific genetic background, combined with infectious triggers, will start the inflammation process and imbalance of pro- and anti-inflammatory responses. The most recent studies highlight the importance of gut microbiome in this process.

It remains unknown if travelers have a higher chance of developing IBD than the rest of the population. Stool and blood samples should raise suspicion of the condition. A colonoscopy with biopsy will show the definitive diagnosis.

Colorectal cancer

With all those exotic microbes in mind and the fact we’re talking about the traveler, we often forget to include all the possibilities.

Bloody diarrhea is not uncommon, especially after traveling in South Asia. However, even if it looks like infectious colitis (inflammation of the large intestine), a full colonoscopy should be performed in patients 50 years and older.

The average lifetime risk of colorectal cancer is more than 5% in Western countries, and early detection is one of the most important factors in treatment.

Summary

Every diarrhea lasting longer than 14 days should receive medical attention.

Simple diagnostic methods such as questioning (symptoms, place of travel, activities, medication…), examining the patient, and blood and stool samples will direct the next steps and, in most cases, will resolve the issue with the right treatment.

Although it’s hard to avoid traveler’s diarrhea altogether, its fast treatment can prevent the complications described here.

Learn how to get rid of acute diarrhea fast.

Follow basic rules to prevent parasitic infection from contaminated water and food.

Resources

Keystone, J. S., Kozarsky, P. E., Connor, B. A., Nothdurft, H. D., Mendelson, M., & Leder, K. (2018). Travel Medicine E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2014-0-02041-2

Soonawala, D., van Lieshout, L., den Boer, M. A., Claas, E. C., Verweij, J. J., Godkewitsch, A., Ratering, M., & Visser, L. G. (2014). Post-travel screening of asymptomatic long-term travelers to the tropics for intestinal parasites using molecular diagnostics. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 90(5), 835–839. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.13-0594

Steffen, R., Hill, D. R., & DuPont, H. L. (2015). Traveler’s diarrhea: a clinical review. JAMA, 313(1), 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.17006

Ross, A. G., Olds, G. R., Cripps, A. W., Farrar, J. J., & McManus, D. P. (2013). Enteropathogens and chronic illness in returning travelers. New England Journal of Medicine, 368(19), 1817-1825. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1207777

Freedman, D. O., Weld, L. H., Kozarsky, P. E., Fisk, T., Robins, R., von Sonnenburg, F., Keystone, J. S., Pandey, P., Cetron, M. S., & GeoSentinel Surveillance Network (2006). Spectrum of disease and relation to place of exposure among ill returned travelers. The New England journal of medicine, 354(2), 119–130. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa051331

Connor, B. A. (2005). Sequelae of traveler’s diarrhea: focus on postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Clinical infectious diseases, 41(Supplement_8), S577-S586.

Connor, B. A. (2013). Chronic diarrhea in travelers. Current infectious disease reports, 15, 203-210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-013-0328-2

Duplessis, C.A., Gutierrez, R.L. & Porter, C.K. Review: chronic and persistent diarrhea with a focus in the returning traveler. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines 3, 9 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40794-017-0052-2

Barrett, J., & Brown, M. (2018). Diarrhoea in travellers. Medicine, 46(1), 24-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpmed.2017.10.001.

Shlim, D. R., Hoge, C. W., Rajah, R., Scott, R. M., Pandy, P., & Echeverria, P. (1999). Persistent high risk of diarrhea among foreigners in Nepal during the first 2 years of residence. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 29(3), 613–616. https://doi.org/10.1086/598642

Disclaimer:

The information provided in this blog post is for general informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any health problem. The use or reliance on any information provided in this blog post is solely at your own risk.