If you’ve flown through more than 2 time zones, you’re likely familiar with jet lag. Having trouble sleeping, or the opposite, being sleepy all the time. You may have noticed that different flights result in various issues and symptoms.

While your travel buddy may have felt fresh and ready to explore that temple or surfed at 8 am, you may have been stuck in bed with a headache and low energy for days.

This article will explore why jet lag happens, how the body and brain react, and whether flight direction matters (Spoiler alert: It does!).

In This Article

What does it even mean

Jet lag is a circadian rhythm disorder. It belongs to a larger group of health problems associated with disruptions in the 24-hour sleep–awake cycle.

It is characterized by excessive sleepiness or insomnia (inability to sleep), fatigue, digestion problems, etc., that arise after crossing at least 2 time zones fast. At the same time, the condition can’t be explained by other disorders (such as neurological and mental health).

More time zones crossed equals more negative feelings that last longer.

Jet leg symptoms – it’s not just about insomnia

One would think that finally arriving at our dream destination after a 12-hour flight, all the beauty and joy would cancel out the shock your body just had.

Packing, driving to the airport, waiting in lines, being cramped and sitting in one position for hours, then eating junk food because of overpriced food at the airport while having a layover. And all of this while having constant AC on, dehydrated from the cabin air.

On top of this, you end up in a wet hot climate with nobody speaking your language, while just a few hours earlier you were wearing a jacket on your way to work.

You can feel nausea, tiredness, stress, headache, and mood swings, but it’s all just travel fatigue, which results from the discomfort on the way.

The symptoms of jet lag are similar and can be hard to distinguish, but the cause is different.

Sleep problems

- Having trouble falling asleep (after flying east)

- Waking up early not well rested (after a westward flight)

- Waking up often during sleep

Physical problems

- Higher frequency of defecation, change in consistency of the stools

- Lack of appetite, problems with digestion

- Headache

- Lower physical performance (muscle strength, stamina)

Mental problems

- Irritability

- Decreased ability to concentrate

- Mood swings

Why is our body going crazy

Sadly, our ancestors didn’t fly intercontinental.

Without going into too much detail, let’s explain how our internal body clock works.

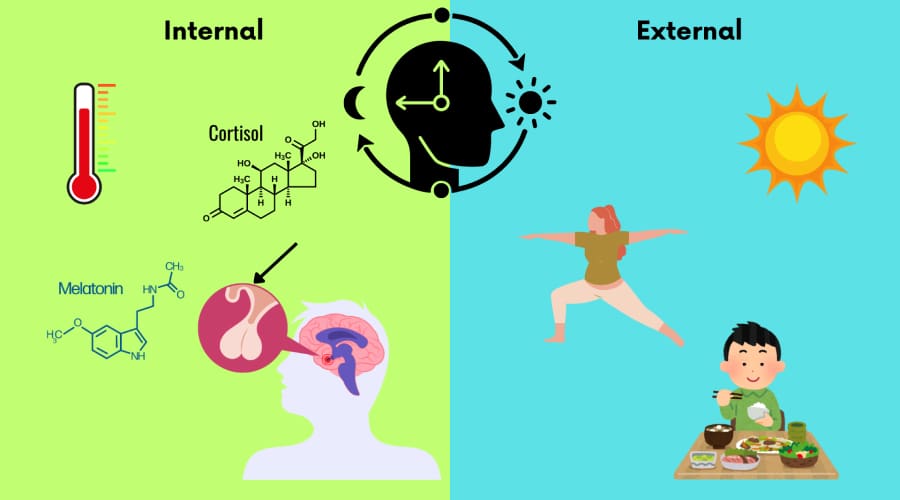

The center for circadian rhythms is in the hypothalamus. There are many stimuli in both directions affecting the rhythm, so let’s divide them into 3 categories:

Body clock, internal signals, and external signals

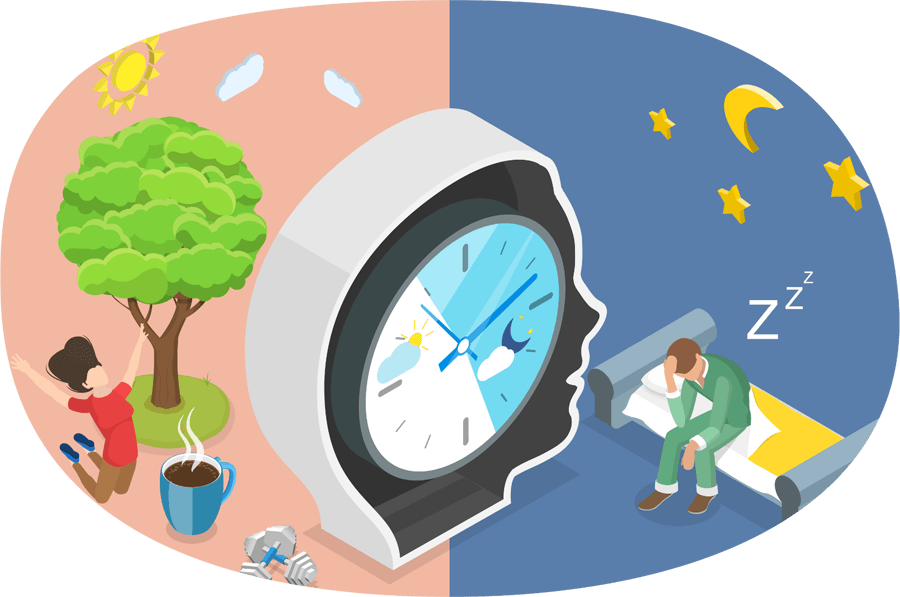

Body clock

This is a highly complicated topic. These are cyclic interactions between clock genes and clock proteins. What is interesting is that on its own, one period is about 24,5 hours long. This would result in a constant shift in the cycle. And it does! In experiments and with people with an inability of light detection. That’s why we use other stimuli to synchronize.

Internal signals

Core body temperature (lowest around 2 hours before waking up)

Hormones such as:

- Cortisol – highest level is before waking up

- Melatonin – secreted by the pineal gland for 10 to 12 hours. Its task is to modulate the nocturnal state and reduce core body temperature. It’s not necessarily associated with sleep. Nocturnal species secrete it at night while being active. It acts as a kind of “darkness” signal for the body, and therefore, it is no surprise that light suppresses melatonin secretion.

External signals

Light exposure – This is the most important one. There are direct pathways from the eye to the circadian rhythm center sending information about daytime and secondary to suppress secretion of Melatonin.

Exercise and eating a meal have shown little effect on circadian rhythms.

Social interactions and even information about the time do not affect our 24-hour cycle.

The flexibility of the circadian rhythm evolved because of seasonality and changes in the length of the day and night throughout the year. For this, our body is prepared perfectly. But for 8 hours’ time change in one day? Sadly, not that flexible. That’s a completely new thing for which we’re unprepared.

The novelty of the last century is also using artificial light exposure late at night or not getting enough sunlight early in the morning. That can make you feel jet lag without setting one foot on the plane. That’s what Andrew Huberman argues in some of his podcasts I highly recommend.

Summary:

Our internal body clock keeps one day-night cycle at around 24.5 hours. The exact length is adjusted mostly by the timing of melatonin secretion and light exposure.

This system offers some flexibility and can adjust for one or two hours based on the stimuli, but after changing 6 time zones, looking at your watch won’t help. Your body remembers the time of your departure destination even if you don’t.

East or West – which one is the best?

First, I must apologize for that cringe-worthy rhyme so we can continue.

The answer gets back to the main issue – sleep.

West

When flying westward, let’s say from Thailand to Germany (5-hour difference), your day gets longer. So, if you hopped on a flight after waking up at your regular time, you arrived in Germany at 6 pm local time.

You’re already sleepy because, at the place of your departure, the time is 11 pm, which is your bedtime (and also your body clock time). Of course, you’re tired from the travel too. You fall asleep at your hotel at 8 pm, waking up at 4 am. If you’re going on a sunrise hike, that’s great, but otherwise, not so much.

The smart thing to do would be to resist the urge to sleep for a few hours, then hopefully wake up not so early. Our bodies have experienced staying up longer than usual, both in our lives and in our ancestors’ lives, and that’s why it’s quite easy. There are a lot of stimulants to help this too like coffee or exercise.

East

When flying eastward, from New York, USA to UK (5-hour difference) your day gets shorter.

The same scenario. You wake up as usual, go straight to the airport, and travel for around 10 hours until you get there. It’s midnight already, but your internal clock and previous destination say 7 pm. You can’t just fall asleep on a command.

Even if you’re tired as hell, it might be even harder to fall asleep. You’re finally sleeping at 3 am, waking up at 10 am, and guess what? There is already a huge line on the London Eye. Or maybe you set the alarm clock to 7 am, and now you’re walking through London like a zombie.

Now these are just to illustrate the time shift and the fact that it’s easier to make yourself not fall asleep (traveling westward) than to do so (traveling eastward). There are countless other situations including layovers, crossing 8 or 10 time zones entirely missing the night, and so on.

Can it be over yet?

So how long does jet lag last? It’s highly individual and depends on lots of factors such as direction. On average, it takes an equal number of days as 2/3 of time zones crossed. So, for 6 time zones the recovery and the calibration of your internal clock will take around 4 days. For 10 time zones, it’s 6 to 7 days.

That’s a crazy amount of time spent uncomfortable. Especially if you’re on a vacation or a business trip that lasts one or two weeks.

But don’t worry. With the correct intervention before takeoff and after landing at your destination, you can shorten the duration of jet lag drastically.

Resources

Waterhouse, J., Reilly, T., Atkinson, G., & Edwards, B. (2007). Jet lag: trends and coping strategies. Lancet (London, England), 369(9567), 1117–1129. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60529-7

Sack R. L. (2009). The pathophysiology of jet lag. Travel medicine and infectious disease, 7(2), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2009.01.006

Disclaimer:

The information provided in this blog post is for general informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any health problem. The use or reliance on any information provided in this blog post is solely at your own risk.