Malaria is a potentially fatal infectious disease spread by mosquitoes. Although great advances have been made in controlling it, it remains a concern in most tropical and subtropical regions.

In 2023, there were an estimated 263 million malaria cases and 597,000 malaria deaths in 83 countries. 94% of the cases and 95% of the deaths occurred in Africa, with West Africa carrying the highest burden.

Different control mechanisms and recommendations exist for the local and traveler populations. I’ll (of course) focus on travelers in this article. For example, adult travelers are at a much higher risk of severe illness than adult locals because of their lack of immunity.

This blog will help you understand how malaria is transmitted, recognize its symptoms, prevent infection, and choose the right prophylaxis.

In This Article

What Is Malaria? Understanding the Disease

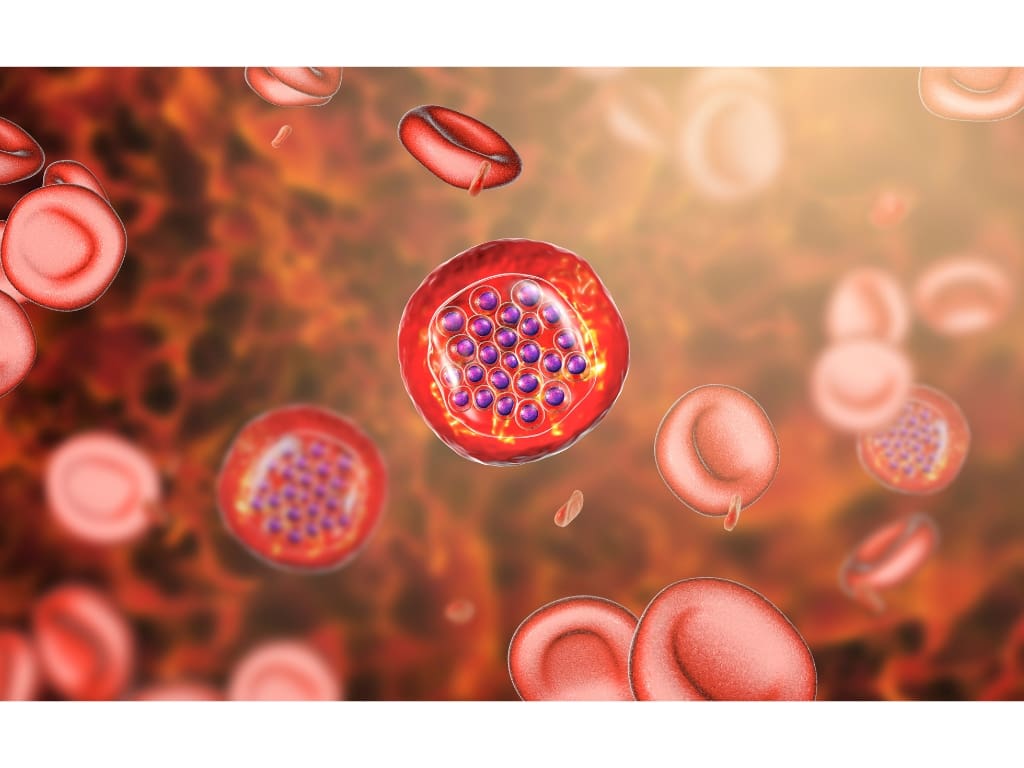

Malaria is caused by parasites of the genus Plasmodium, transmitted through the bites of infected Anopheles mosquitoes.

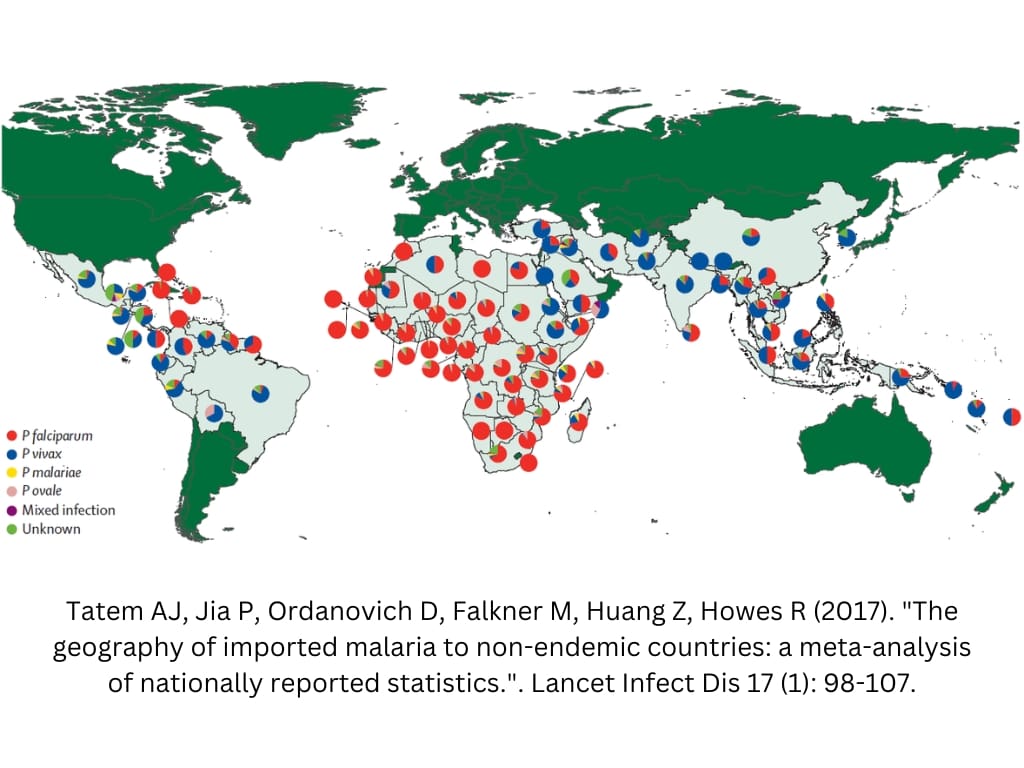

Five species are known to infect humans, all presenting as febrile illnesses and other symptoms, impossible to differentiate without blood examination. All of them can progress to a severe illness and cause death, but one species, Plasmodium falciparum, does so more often and more quickly.

Each species is different in its geographical distribution, length to the onset of symptoms, and sensitivity to antimalarial drugs.

How Does Malaria Spread? The Malaria Transmission Process

Only a female Anopheles mosquito can spread malaria. These mosquitoes become carriers after feeding on a person infected with malaria.

Once inside the mosquito, the parasite undergoes development before being transmitted to another host. The whole cycle is more complicated than in viral diseases like Yellow Fever or Dengue, where the virus is just moved from one place to another.

Transmission is influenced by various factors, including the mosquito species, environmental conditions, and human behaviors.

Stagnant water, common in tropical climates and even more common in the rainy season, serves as a breeding ground for mosquitoes. Poor housing and limited access to protective measures amplify the risk in rural areas.

In Africa, the risk of Malaria is 8 times higher in rural vs. urban areas.

Anopheles mosquitoes are most active at dawn, dusk, and throughout the night.

That doesn’t mean they can’t be active during the day. They can, along with other mosquito species, potentially carrying other infections. That’s why mosquito protection is needed day and night.

The activity varies based on the climate and specific subgroups of mosquitoes. In Africa, the peak hours are after midnight, while in parts of South America and Southeast Asia, it is in the evening. Forested areas or very cloudy days increase the risk of daytime activity.

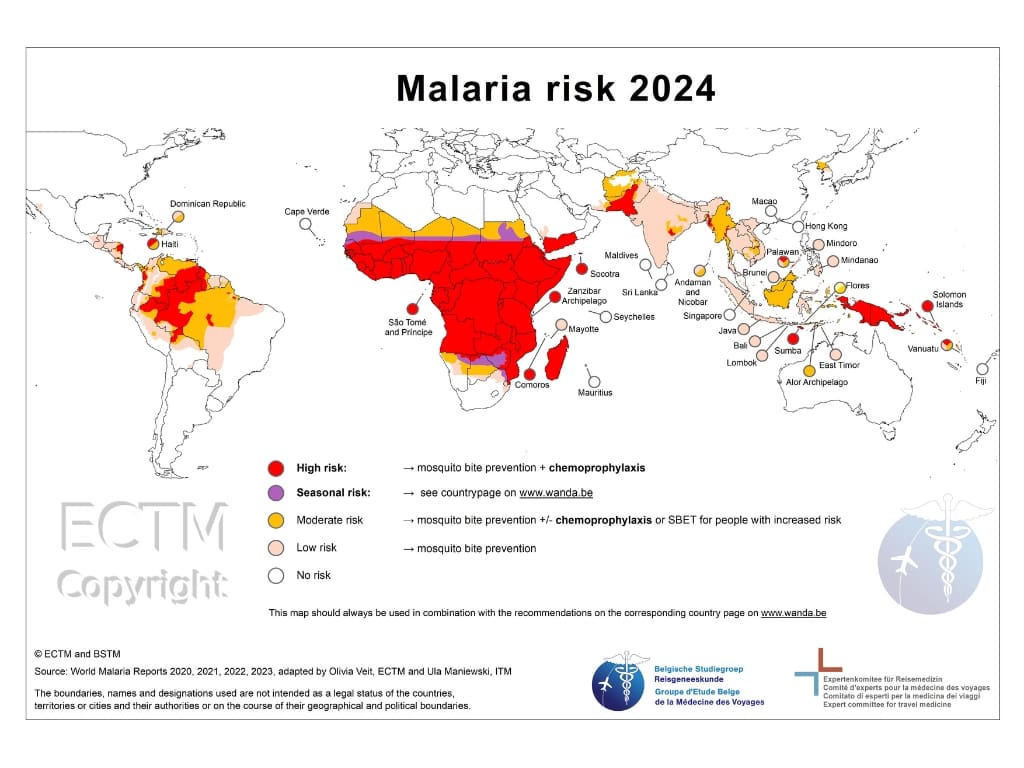

Where Is Malaria a Risk? Global Malaria Hotspots

Malaria is endemic in parts of Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Oceania. The risk is particularly high in sub-Saharan Africa, where Plasmodium falciparum dominates.

Data reveals that travelers to Africa are 4 – 20 times more likely to get Malaria compared to Asia or the Americas.

Canadian statistics highlight a risk rate of 2.26 per 1,000 travelers to Africa, while the rate was just 0.06 for Asia and 0.018 for the Americas.

CDC report of 2,078 cases of malaria from 2016 shows where the Americans got malaria the most. 85% in Africa, 9% in Asia, 5% in the Caribbean and the Americas, and 1% in Oceania or the Eastern Mediterranean.

The optimal climate for Malaria transmission is 68°F to 86°F (20°C to 30°C) and high humidity. Disease control measures in each country play a considerable role in the long term, while rainfall, monsoons, and floods have a short-term impact.

The risk of malaria has significantly decreased in many parts of Asia over the years, leading many authorities to no longer recommend prophylaxis for travelers to these regions.

You can find the list of countries and territories with malaria transmission on this CDC website.

It is also on the UK TravelHealthPro country pages, including a map of the regions.

Note: Statistics from the traveler population are different from the native population.

Fever After Travel? Recognize Malaria Symptoms Early

Symptoms in the nonimmune traveler typically arise 8 – 14 days after an infectious bite, but this is very variable. In Falciparum species (frequent in Africa), apparent symptoms occur within 1 – 3 months after travel.

In vivax species, it’s typically longer because this parasite has a dormant stage. It can either relapse (return in some time after the first attack) or, in the case of taking antimalarial prophylaxis, appear 2 months or later after stopping the medication.

This is apparent in the fact that approximately 90% of travelers have their first symptoms of malaria only after they’ve returned home.

Therefore, any fever in the first year after returning from a region with malaria transmission should be promptly examined to rule out malaria.

The same applies to fever after the seventh day in the malaria region.

Recognizing malaria symptoms early is crucial. Common signs include:

- Fever, chills, and sweats.

- Headache and muscle aches.

- Nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea.

- Fatigue, malaise, and cough.

Fever is a hallmark symptom of malaria and is often preceded by 1–2 days of vague symptoms such as abdominal discomfort, headache, muscle aches, and general malaise. Surprisingly, cough is also common, occurring in 20%–50% of cases.

In non-immune individuals, the classic fever cycles associated with the malaria parasite life cycle are rare (every 24, 48, or 72 hours, when the cycle is completed, the toxins are released with bursting red blood cells). Instead, daily paroxysms (sudden and intense attacks or bursts of symptoms) are more typical.

These episodes may begin in the late afternoon with severe vomiting and intense shivering that lasts for hours, followed by a high fever (102.2° – 106.7°F / 39° – 41.5°C) and profuse sweating. By early morning, the fever subsides, leaving the patient exhausted but finally able to rest.

Severe malaria can manifest as impaired consciousness, respiratory distress, jaundice, seizures, kidney failure, coma, or multi-organ failure.

The mortality rate for uncomplicated malaria with appropriate treatment is around 0.1%.

For severe malaria, it jumps to 15-20% and reaches 50% in pregnant women. That translates to 1, 15, and 50 deaths per 1000 cases. The vivax species (predominant in Asia and the Americas) is approximately 10 times less deadly than falciparum (predominant in Africa).

What to Do If You Suspect Malaria During or After Travel

Fever after the seventh day of traveling in a malarial region is an emergency and should be examined as soon as possible.

Other symptoms, like cough or diarrhea, can suggest a respiratory or gastrointestinal infection, but they are common in malaria, too. Get checked in a local health care facility where they have experience diagnosing malaria.

Prompt treatment is essential to achieve the best outcomes and prevent the illness from worsening.

It consists of antimalarial drugs and supportive care, including hydration, fever control, and more.

Based on the patient’s symptoms and blood results, it may take just 24 hours of observation in the hospital, as the drugs can be taken orally. However, if the patient is not getting better, the treatment may take up to 14 days and even longer in case of severe malaria.

Standby Emergency Treatment for Malaria

In some cases, travelers may be prescribed standby emergency treatment before departure. These may be used by travelers when needed.

There are different opinions on the effectiveness and use cases of this approach. Studies on travelers carrying the treatment and using rapid diagnostic tests (like pregnancy tests or COVID rapid tests, but using drop of blood) for self-management found many problems. A high percentage of travelers:

- failed to use and read the test results correctly

- haven’t started the treatment when they should have

- didn’t seek medical help as soon as possible

UK guidelines don’t recommend using these rapid tests, and both the UK and the US authorities recommend standby treatment only as a supplement to malaria prophylaxis, not as a replacement.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the use of Standby Emergency Treatment in the following scenarios:

- Travelers in remote areas who cannot access medical care within 24 hours of fever onset.

- Occupational travelers frequently making short visits to malaria-endemic areas over an extended period.

- Short-term travelers spending a week or more in remote rural regions with a low risk of malaria infection.

Drugs for self-treatment have to be different than those used for prophylaxis by individual travelers, and travelers must get to the hospital as soon as possible after the symptoms arise.

Prevention Strategies: How to Avoid Malaria

Prevention of malaria is often explained as a 4 step approach in the ABCD acronym.

- Awareness of the risk

- Bite prevention

- Chemoprophylaxis (drugs for malaria prevention)

- Diagnosis (early diagnosis and treatment)

Awareness of the risk

Being aware of the risk is essential for all the other steps. For example, you don’t need much of mosquito preventive measures in Canada or Sweden.

There is a very low risk of malaria in many parts of South America. Still, you should protect yourself against mosquitoes because of Zika, Dengue, or Yellow fever, and you should also know the risk of malaria is very high in West Africa.

You can find the areas with risk here, here, or at the pre-travel appointment at the clinic.

Bite prevention

Bite prevention is crucial in most tropical and subtropical regions to protect against mosquitoes, carrying not just malaria. However, nighttime protection is emphasized for Anopheles mosquitoes.

It consists of:

- Insect repellent—a minimum of 20% DEET or 20% Icardin works best; a higher content of DEET will last longer, so you don’t have to apply it so often. UK guidelines recommend 50% DEET for malarious areas. Natural repellents like citronella or cinnamon will not protect you. The only plant-based repellent approved is “Eucalyptus citriodora oil, hydrated, cyclized.”

- Bed net – All travelers to malaria-endemic areas should use mosquito nets unless staying in rooms with sealed windows, doors, or functioning air conditioning. Nets should be intact, tucked under the mattress, and taut. Insecticide-treated nets offer extra protection by preventing bites through the net and deterring mosquitoes from surviving near potential tears.

- Long-sleeved clothing – Clothing can be impregnated with insecticide, usually permethrin. DEET can also be used on clothes, but the effect is shorter, and it may melt synthetic fabrics.

- Air-conditioned and screened room – Air conditioning reduces mosquito bites by lowering nighttime temperatures and increasing airflow, while ceiling fans help deter mosquitoes. Before dusk, you can spray the room with a pyrethroid-based insecticide. At night, use plug-in devices with liquid insecticides or pyrethroid mats where electricity is available.

Malaria Chemoprophylaxis

Chemoprophylaxis is a fancy word for medication used to prevent a disease.

Quinine, derived from the bark of the Cinchona tree, was the first known treatment for malaria. Used by tribes in Ecuador and Peru to treat fevers, its antimalarial properties were first recorded in 1633 by an Augustine monk in Peru.

Fun fact: Quinine powder was initially consumed by mixing it with wine or dissolving it in water, creating what we now call “tonic water.” However, its intense bitterness made it difficult to drink in concentrations that were effective against malaria.

To make it more palatable, British colonial officers in malaria-stricken India began adding sugar, lime, and gin, giving rise to a drink that remains popular today: the gin and tonic.

I know what you think about now. But no, levels of quinine in tonic are very low nowadays and have no effect on the parasites.

Quinine remained the sole malaria treatment until the 1920s, when German scientists developed synthetic antimalarials like Atabrin, followed by chloroquine during WWII.

Wide use of chloroquine resulted in resistance in most malaria areas, and the only places where falciparum species remain sensitive are Central America, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic.

Primaquine and Tafenoquine are safe and effective, but they are rarely used for chemoprophylaxis and are not even approved for prevention in some countries.

This is mainly because of severe adverse effects in people who lack a specific enzyme (G6PD). Testing this enzyme is expensive and time-consuming, and therefore, its use is limited.

The three most used drugs for malaria chemoprophylaxis are:

Atovaquone/Proguanil (Malarone®)

Highly effective against P. falciparum and offers the advantage of a short post-travel regimen (7 days). It’s well-tolerated, with minimal side effects such as mild gastrointestinal discomfort. However, it is pretty expensive.

Doxycycline (Acticlate®, Adoxa®…)

Affordable and versatile, it also protects against other infections like leptospirosis. Adverse events include photosensitivity (exaggerated sunburn), nausea, diarrhea, or vaginal candidosis. It has to be taken daily for four more weeks after leaving the risk area.

Mefloquine (Lariam®)

May be better for long-term travel, as it requires weekly dosing. However, it’s associated with neuropsychiatric side effects, such as vivid dreams or anxiety, in a small percentage of users. It can be started 2-3 weeks before travel to monitor tolerance.

As you can see, they all have different dosages, adverse effects, contraindications, interactions with other drugs, and so on. Ask your GP or travel health specialist for details to choose what best suits you.

You can also read an article where I go into detail about malaria chemoprophylaxis.

Malarone® seems to have the best tolerability, with the least frequent side effects and the least number of situations where it can’t be prescribed.

Why Malaria Prophylaxis Is Essential for Travelers

Follow the recommendations in high-risk areas where malaria chemoprophylaxis is advised.

Remember, malaria can be fatal, and travelers are at high risk as unimmune individuals. Because of the parasite’s specific life cycle, the prescribed dosage must be followed, including continuing medication after your trip ends.

Although the prevention is not 100% effective, almost all travelers who got sick with malaria either didn’t use the prophylaxis, skipped doses, or stopped the medication early.

Buying the drugs abroad may be cheaper, but travelers are advised not to do so.

Antimalarial drugs may be counterfeit, substandard, or improperly stored, reducing their effectiveness and potentially putting your health at risk. You should also have protective blood levels of the drug already when entering the risk area, which cannot be achieved without starting at home.

Meta-analysis of 96 studies with data on tens of thousands of drug samples found that 19.1% of antimalarials in low- and middle-income countries worldwide were substandard or falsified.

Drugs for the treatment of Malaria sold in the illegal markets in Benin were tested, with a staggering 42.5% being substandard.

High-Risk Groups: Special Considerations for Travelers

Who is at higher risk of getting Malaria?

Backpackers and budget travelers

It depends on all of the factors mentioned before, like the number of cases in the region and the level of protection of the traveler. Even the way of travel matters, as backpackers and travelers on a low budget often stay in cheap accommodations with no mosquito protection, in rural areas and in closer contact with the local population.

Travelers on self-made trips were 9 times more likely to get malaria than those on organized tours.

Visiting friends and family (VFR)

People who left their home country in malaric region to live in Europe or North America are at the highest risk of malaria when traveling. They may have moved a generation ago or just one or two years ago; either way, they are not immune to malaria but might dangerously believe they’re protected.

Compared to other travelers, they are less likely to seek pretravel consultation and to take chemoprophylaxis. They overestimate their natural protection and underestimate the risk. This might be potentiated by relatives in the malaria country, who are in a completely different position from the perspective of epidemiology and immunity.

When divided by purpose of travel, this group consistently has the highest number of imported malaria cases.

Here’s some data to convince you, or your friends who might fall into this group, why malaria protection is so important.

In the UK, 80% of the imported malaria cases are VFR. In the USA, it was 70% in 2017.

In a multinational study, VFRs were 8x, 3x, or 2x as likely to get diagnosed with Malaria traveling to Africa, Latin America, or Asia.

In children, these numbers are even higher.

Long-term travelers

The risk of malaria also rises with the length of the stay. Staying for 3 months has a 6 times higher risk of getting sick compared with a 2-week visit.

All of the frequently used drugs have been tested in use for months, up to 2.5 years. While the risk of malaria rises, the risk of new adverse reactions to the drug falls.

Children and pregnant

Infants, young children, and pregnant women have a much higher risk of severe malaria and death. Extra caution and re-evaluation of a need to travel might be needed in high risk areas.

The elderly and those with chronic illnesses

The risk of malaria being deadly is higher in older adults, immunocompromised people, and people with serious chronic illnesses.

Conclusion: Stay Prepared, Stay Safe

The worst thing about the prevention of any disease is that it has terrible marketing.

When it is successful, nothing happens.

That is why I use data to educate and why it’s important to be prepared—not to be stressed out or to avoid travel to places that have risks.

Preparation gives you the mental and physical strength to fully enjoy your trip and the tools to manage unexpected situations.

Get ready by reading other blog posts and following us on social media!

Resources

Travel Medicine, 4th Edition – December 13, 2018, Authors: Jay S. Keystone, Phyllis E. Kozarsky, Bradley A. Connor, Hans D. Nothdurft, Marc Mendelson, Karin Leder, Language: English, Hardback ISBN: 9780323546966

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023). CDC Yellow Book 2024: Health Information for International Travel. Oxford University Press.

Chiodini PL, Patel D, Goodyer L, Frise C, Mabayoje D, Aggarwal D. Guidelines for malaria prevention in travellers from the United Kingdom, 2024. London: UK Health Security Agency; October 2024.

Zekar, L., & Sharman, T. (2023). Plasmodium falciparum malaria. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.

Weiss, D. J., Lucas, T. C., Nguyen, M., Nandi, A. K., Bisanzio, D., Battle, K. E., … & Gething, P. W. (2019). Mapping the global prevalence, incidence, and mortality of Plasmodium falciparum, 2000–17: a spatial and temporal modelling study. The Lancet, 394(10195), 322-331.

Milner, D. A. (2018). Malaria pathogenesis. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine, 8(1), a025569.

Idro, R., Jenkins, N. E., & Newton, C. R. (2005). Pathogenesis, clinical features, and neurological outcome of cerebral malaria. The Lancet Neurology, 4(12), 827-840.

Plewes, K., Leopold, S. J., Kingston, H. W., & Dondorp, A. M. (2019). Malaria: what’s new in the management of malaria?. Infectious Disease Clinics, 33(1), 39-60.

Askling, H. H., Nilsson, J., Tegnell, A., Janzon, R., & Ekdahl, K. (2005). Malaria risk in travelers. Emerging infectious diseases, 11(3), 436.

Voumard, R., Berthod, D., Rambaud-Althaus, C., D’Acremont, V., & Genton, B. (2015). Recommendations for malaria prevention in moderate to low risk areas: travellers’ choice and risk perception. Malaria journal, 14, 1-7.

Tatem AJ, Jia P, Ordanovich D, Falkner M, Huang Z, Howes R (2017). “The geography of imported malaria to non-endemic countries: a meta-analysis of nationally reported statistics.“. Lancet Infect Dis 17 (1): 98-107. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30326-7

Ozawa, S., Evans, D. R., Bessias, S., Haynie, D. G., Yemeke, T. T., Laing, S. K., & Herrington, J. E. (2018). Prevalence and estimated economic burden of substandard and falsified medicines in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA network open, 1(4), e181662-e181662.

Baba-Moussa, F., Bonou, J., Ahouandjinou, H., Dougnon, T. V., Kpavode, L., Raimi, N., … & Baba-Moussa, L. (2015). Quality control of selected antimalarials sold in the illicit market: an investigation conducted in Porto-Novo City (Republic of Benin). Advances in Bioscience and Biotechnology, 6(10), 637-644.

Pinsent A, Read JM, Griffin JT, et al. Risk factors for UK Plasmodium falciparum cases. Malar J 2014;13:298.

Ladhani S, Aibara RJ, Riordan FA, et al. Imported malaria in children: a review of clinical studies. Lancet Infect Dis 2007;7:349–57.

Schlagenhauf, P., Tschopp, A., Johnson, R., Nothdurft, H., Beck, B., Schwartz, E., … & Steffen, R. (2003). Tolerability of malaria chemoprophylaxis in non-immune travellers to sub-Saharan Africa: multicentre, randomised, double blind, four arm study. Bmj, 327(7423), 1078.

Disclaimer:

The information provided in this blog post is for general informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any health problem. The use or reliance on any information provided in this blog post is solely at your own risk.