Planning a trip to a malaria-endemic region? Don’t let malaria derail your adventure. This guide dives deep into the medications used for malaria chemoprophylaxis and standby emergency treatment (SBET).

Learn about drug dosages, adverse effects, contraindications, special advice for children, pregnant and breastfeeding individuals, interactions with medications like warfarin, and even cost comparisons.

If you want to learn more about malaria in general, start here.

In This Article

Chemoprophylaxis: Preventing Malaria Before It Starts

Malaria chemoprophylaxis involves preventive medications taken before, during, and after travel to malaria-risk regions.

All antimalarials (like every medicine) have the risk of side effects. In 1%—7% of travelers, these events lead to discontinuing the medication.

Another problem is poor adherence to the prescribed dosage after returning home. However, because of the malarial parasite’s life cycle, post-travel intake is necessary to ensure protection.

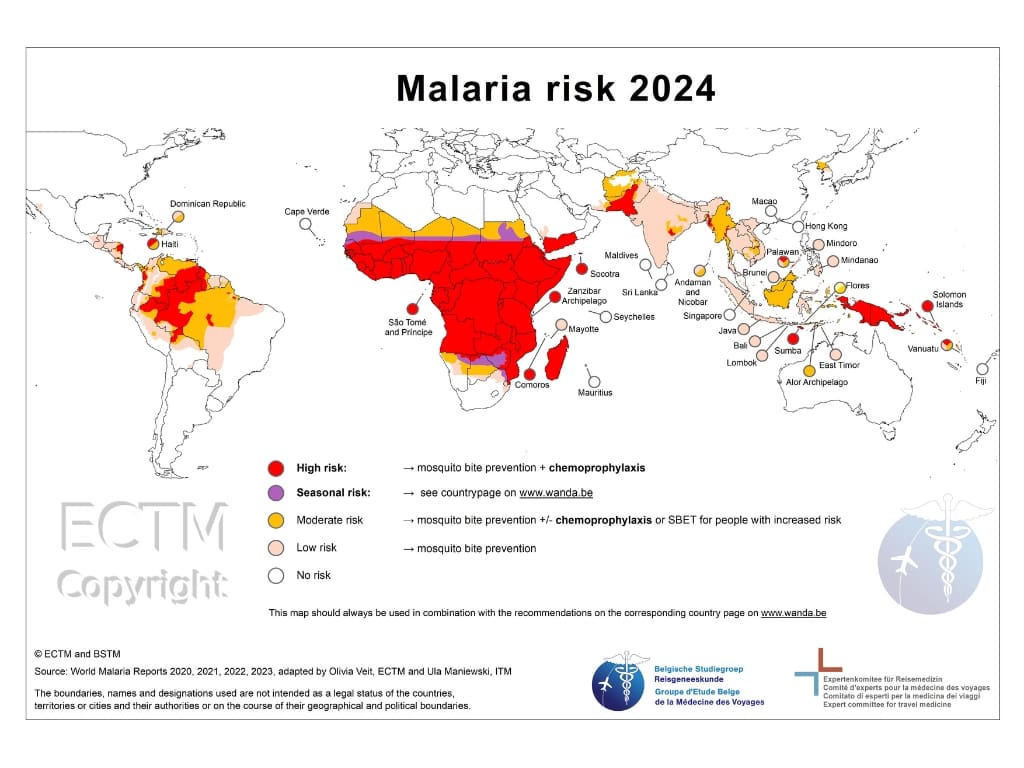

CDC, UKHSA, and other national authorities usually have a list of countries and the risk of malaria there, often divided into smaller regions. They assess whether malaria prophylaxis or just bite avoidance and malaria awareness is recommended.

Other factors, such as season, itinerary, accommodation, and traveler’s health status, play a huge role in the decision process. I’ve focused on these in another blog post. Consult a travel health specialist for tailor-made advice.

Here’s everything you need to know about the most commonly used drugs.

Atovaquone-Proguanil (Malarone™)

Atovaquone/proguanil has emerged as a well-tolerated and effective option for malaria prophylaxis in non-immune travelers. It’s the one most prescribed for travelers in developed countries.

- Dosage:

- Adults: 1 tablet daily (250 mg atovaquone/100 mg proguanil).

- Children: Dose based on weight.

- Start 1–2 days before travel, continue daily during travel, and for 7 days post-travel.

- Adverse Events:

Significantly better tolerated than mefloquine and chloroquine and better tolerated than doxycyclin.

The most commonly reported adverse events are gastrointestinal, which can often be reduced by taking it with food.

- Common: Gastrointestinal upset, abdominal pain, vomiting, headache.

- Rare: Severe skin reactions like Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (<1 in 10,000 users).

- Discontinuation Rate: 0–2%, making it one of the most tolerable chemoprophylactics

- Contraindications: Can’t be used in severe renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min). History of hypersensitivity to one or both active substances.

- Special Considerations:

- Pregnancy/Breastfeeding: Generally not recommended due to limited safety data.

- Children: Approved for children over 5kg in the US and over 11kg in some other countries.

- Warfarin Users: May alter the anticoagulant effect; UK guidelines recommend checking INR before and after 1 week of taking the drug, therefore starting early enough before departure

- Drug Interactions: Avoid concurrent use with rifampicin, rifabutin, tetracyclines, and metoclopramide, as they reduce efficacy. Atovaquone lowers the concentration of azithromycin (antibiotics often prescribed for traveler’s diarrhea) and increases levels of protease inhibitors (drugs used in HIV patients).

- Cost: Approximately $6–$10 per daily tablet, one of the more expensive options.

Doxycycline (Vibramycin®, Acticlate®...)

Doxycycline is an effective antimalarial that also provides protection against some other travel-related infections.

- Dosage:

- Adults: 1 tablet of 100 mg daily.

- Children: Dose based on weight.

- Start 1–2 days before travel, continue daily during travel, and for 4 weeks post-travel.

- Older recommendations suggest avoiding milk at the time of ingestion, but recent studies indicate no influence of milk on absorption.

- Adverse Events:

- Gastrointestinal upset (4-33%), including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea

- Photosensitivity (reported rates range from less than 7% to 21% or more). These range from mild paresthesias (tingling or “pins and needles” sensation) or exaggerated sunburn in exposed skin to photo-onycholysis (sun-induced separation of nails), severe erythema (redness of the skin), blister formation, and (extremely rarely) Stevens-Johnson syndrome. The majority of reactions are mild, and the occurrence can be lowered by proper sunscreen use.

- Esophagitis and Esophageal ulceration are rare. Take with a full glass of water and remain upright for 30 minutes to avoid irritation of the esophagus.

- Increased risk of oral and vaginal Candida (yeast) infections in predisposed individuals, especially those with a history of such infection.

- Discontinuation Rate: Up to 6% due to adverse effects, particularly gastrointestinal symptoms. However, much of the data comes from older studies using doxycycline hyclate. More recent studies suggest a lower frequency of gastrointestinal adverse events when using doxycycline monohydrate (Monodox®…)

- Contraindications: Tetracycline hypersensitivity/ allergy, pregnancy, breastfeeding, young children

- Special Considerations:

- Pregnancy/Breastfeeding: Contraindicated in pregnancy (skeletal defects) and while breastfeeding (risk of bone and teeth effects).

- Children: Approved for older children, ≥8 years in the US, or ≥12 years in the UK

- Warfarin Users: May increase bleeding risk; close INR monitoring is advised

- Drug Interactions: Absorption reduced by antacids, oral iron, bismuth salts, calcium, cholestyramine or colestipol, and laxatives that contain magnesium; separate doses as much as possible, and at least by 2 hours.

Drugs used in epilepsy treatment may reduce doxycycline levels in the blood.

Decreased efficiency of oral contraceptives (birth control) was reported historically. Current evidence suggests no significant influence on birth control effectiveness. - Cost: Affordable at $0.25–$1.70 per tablet. However, a daily dose for 4 weeks post-travel means 43 doses are needed for a 14-day trip.

Mefloquine (Lariam ®)

Mefloquine has been a widely used antimalarial, but concerns about its neuropsychiatric side effects have led to a decrease in its use or even discontinuation in some countries.

There’s an area of resistance around the Thailand – Cambodia border, so it shouldn’t be used here.

- Dosage:

- Adults: 250 mg once weekly.

- Children: Dose based on weight (e.g., 5–10 kg: 1/8 tablet weekly).

- Start 2–3 weeks before travel (to monitor side effects, but is effective when taken just 1 week before travel), continue weekly during travel, and for 4 weeks post-travel.

- Adverse Events:

- Very common (10% or more): Abnormal, strange or vivid dreams, insomnia.

- Common (1% – 10%): Depression, anxiety, dizziness, headache, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, itching, visual difficulties…

- Rare: Severe neuropsychiatric events such as psychosis or seizures (<1 in 10,000 users).

The presence of neuropsychiatric AEs is very high compared to other antimalarial medications, and they need to be explained to every traveler.

It occurs more frequently in women, possibly caused by higher doses per weight. Children and older adults tolerate mefloquine better, with much fewer side effects.

- Discontinuation Rate: Up to 5% due to adverse effects.

- Contraindications: Hypersensitivity to mefloquine, quinine, or quinidine, a history of blackwater fever (hemoglobinuria as a result of Malaria or antimalarial medication), severe liver impairment, history of depression, psychosis, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, self-endangering tendencies and other psychiatric disorders, epilepsy, and convulsions of any origin.

- Special Considerations:

- Pregnancy: Safe in the second and third trimesters and can be used with caution in the first trimester. Allowed while breastfeeding.

- Children: Allowed to use in children. No syrup exists, so it’s hard to achieve the right dose by dividing adult tablets.

- Divers: Some diving centers and tour organizers may not permit those taking mefloquine to dive. This is because the adverse events could imitate diving-related medical issues such as decompression sickness.

There is no evidence of worse underwater performance, and there have been tests on flying and driving simulators reporting no significant psychomotor impairment.

- Drug Interactions: Avoid taking with cloroquine, quinine, quinidine, halofantrine, or ketoconazole.

- Cost: $3–10 per weekly dose.

Chloroquine (Aralen®)

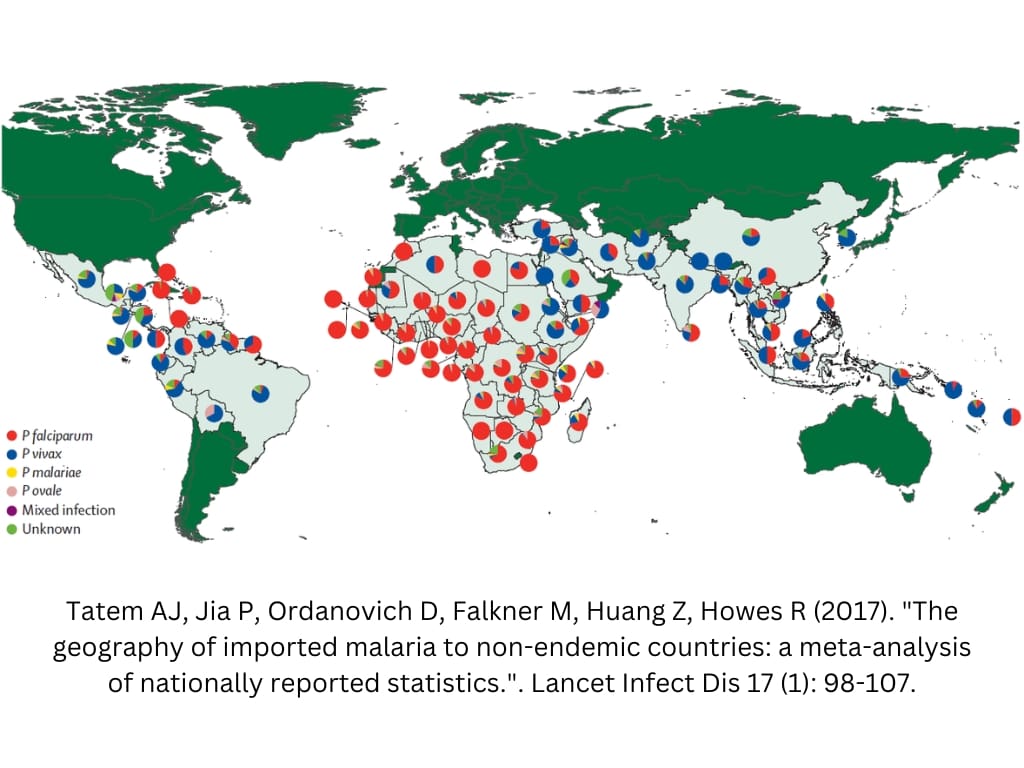

Chloroquine has a long history of use both for treatment and prophylaxis. However, resistance started to arise quickly, and currently, the only regions where it remains effective enough against P. falciparum are Central America north of the Panama Canal, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic.

- Dosage:

- Adults: 300 mg base or 500mg salt weekly.

- Children: 5 mg/kg base or 8.3 mg/kg weekly (max 300/500 mg).

- Start 1 week before travel, continue weekly, and for 4 weeks post-travel.

- Adverse Events:

- Common: Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, hair loss, mood changes.

- Rare: Retinopathy and visual disturbances after prolonged use, low blood sugar.

- Discontinuation Rate: Around 5%.

- Contraindications: Hypersensitivity to chloroquine, Retinopathy, Myasthenia gravis, disorders of the blood-producing organs, history of epilepsy, psychosis, and other disorders of the central nervous system.

- Special Considerations:

- Pregnancy/Breastfeeding: Safe.

- Children: Approved for children.

- Children: Approved for children.

- Drug Interactions: Its absorption is reduced with antacids; separate doses by 4 hours. It can’t be used with amiodaron.

- Cost: Very affordable at $0.50–$2 per weekly dose.

Primaquine

Primaquine has been used for decades for terminal prophylaxis (presumptive use of this drug at the end of the chemoprophylaxis using another drug) and a radical cure for relapsing malaria.

This is used in species of Malaria-causing parasites called Plasmodium vivax and ovale. These two species can remain in a dormant stage in the liver and, after months, cause relapse of acute Malaria. Not every medication is effective against this stage, including none of the three most used drugs for prophylaxis.

It has the best prophylactic effect on P. vivax (majority in Asia and Americas) and a comparably good effect against P. falciparum (widespread in Africa, causing the majority of deaths), but potential severe side effects in groups of people with certain enzyme deficiencies prevent it from wider use. It’s not licensed for prevention in many countries, including the USA.

- Dosage:

- Adults: 30 mg (52.6mg salt) daily. Begin 1 day before entering the malarial area, continue during the stay, and for 7 days after leaving.

- Children: 0.5 mg/kg daily (max 30 mg).

- Adverse Events:

- Common: Nausea, abdominal pain, vomiting, rash, dizziness.

- Rare: Hemolysis in G6PD-deficient individuals (>50% in those affected).

- Discontinuation Rate: Less than 2%

- Contraindications: Individuals with G6PD deficiency (should always be tested), with NADH methemoglobin reductase deficiency, or those receiving potentially hemolytic drugs.

- Special Considerations:

- Pregnancy/Breastfeeding: Contraindicated.

- Children: Limited experience

- It may not be effective in persons who are intermediate metabolizers of CYP 2D6 (liver enzyme).

- Precautions: G6PD deficiency testing is mandatory before prescribing. The amount of people with this deficiency varies by region and ethnicity based on genetics.

Up to 5% of the population may be G6PD deficient, making it the most common enzyme deficiency. It’s more frequent in males and people from Southeast Asia, parts of Africa, and others. - Cost: Approximately $2-$4 per daily dose.

Tafenoquine (Arakoda®)

It is similar to Primaquine but has a longer elimination time, meaning less frequent drug intake is needed.

Data from clinical trials are available, and it has been approved for malaria chemoprophylaxis in the US and Australia since 2018.

- Dosage:

- Adults: 200 mg (2 tablets) daily for 3 days before travel,

200 mg (2 tablets) once weekly during travel (starting 1 week after the last pretravel dose), 200 mg (2 tablets) once after travel (starting 1 week after the last travel dose)

- Adults: 200 mg (2 tablets) daily for 3 days before travel,

- Adverse Events:

- Common: Back pain, headache, gastrointestinal upset.

- Rare: Hemolysis in G6PD-deficient individuals (>50% in those affected).

- Contraindications: Individuals with G6PD deficiency (should always be tested), history of psychiatric disorder, or current psychiatric symptoms.

- Special Considerations:

- Pregnancy/Breastfeeding: Contraindicated.

- Children: Not approved

- Precautions: G6PD testing required.

- Cost: Expensive, at $240–$350 per course (the smallest package is for up to a 4-week trip).

To prescribe Primaquine and Tafenoquine, G6PD (enzyme) deficiency has to be outruled. It’s determined by genetics; therefore, one blood test is enough for life.

It costs $30 – $50 in the US. If you are G6PD deficient, this medication may cause life-threatening hemolysis (destruction of red blood cells).

Standby Emergency Treatment (SBET)

SBET provides self-administered treatment for suspected malaria when medical care is inaccessible.

In some countries (Switzerland, Austria…), SBET is used as an alternative to chemoprophylaxis to low and modrate risk areas with Malaria.

Other countries and experts recommend SBET only to remote areas (more than 24 hours to the nearest medical facility) along with prophylaxis.

Paraphrasing prof. Behrens from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine:

„Recommending SBET makes little sense in current South East Asia and South American low-falciparum transmission destinations.“

He cites data from UK travelers to Southeast Asia that shows the incidence of all malaria to be around 0.1 cases per 100,000 visits and only one case of P. falciparum in 3.5 million visitors to 11 countries.

He further argues that even if we use older data of 0.4 cases of falciparum Malaria per 100,000 visits, we would need to prescribe more than 200,000 doses to treat one case and 20 million doses to save one life.

SBET shouldn’t be viewed as a way to avoid chemoprophylaxis. However, in a Swiss study, when people traveling to low and moderate-risk areas (most of Latin America and Southeast Asia) had to choose by themselves between chemoprophylaxis, SBET, or bite avoidance only, 58% chose SBET, and just 15% chose chemoprophylaxis.

That’s where national guidelines differ, for example, for travelers to the same place, northern Guatemalan department Petén, where amazing Mayan sites can be found. American CDC recommends chemoprophylaxis, UK Health Security recommends bite avoidance only, and some european countries may recommend SBET.

The overall risk of malaria and access to health care should be assessed based on each individual’s itinerary, health, and preferences.

If prescribed, it must be different from the medicine used for chemoprophylaxis and should be used immediately after the onset of fever (after the seventh day in an endemic area).

In this case, the traveler should still get to the hospital as soon as possible.

Artemether-Lumefantrine (Coartem®)

- Dosage:

- Six doses over three days (e.g., 4 tablets initially, then 4 tablets at 8, 24, 36, 48, and 60 hours).

- Six doses over three days (e.g., 4 tablets initially, then 4 tablets at 8, 24, 36, 48, and 60 hours).

- Adverse Events:

- Common: Nausea, dizziness, fatigue, headache, muscle and joint pain.

- Rare: Allergic reactions.

- Special Considerations:

- Avoid in the first trimester unless absolutely necessary.

- Approved for children

- Drug Interactions: Can’t be used with rifampin, carbamazepine, phenytoin

Cost: $150–$170 per full 3-day course.

Atovaquone-Proguanil (MalaroneTM)

It’s not the most effective for SBET, but it’s easily available.

- Dosage:

- For SBET: Four tablets (1,000 mg atovaquone/400 mg proguanil) taken once daily for 3 days.

- For SBET: Four tablets (1,000 mg atovaquone/400 mg proguanil) taken once daily for 3 days.

- Adverse Events, Contraindications, and Special considerations as described earlier

- Cost: $6 – $10 per tablet (12 tablets needed).

Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine (DHA-PPQ)

Not approved for SBET in the US.

- Dosage:

- Dosage is based on body weight:

- 36-<75 kg: 3 x 320mg / 40mg tablets once daily for 3 days

- 75-100 kg: 4 x 320mg / 40mg tablets once daily for 3 days

- 75-100 kg: 4 x 320mg / 40mg tablets once daily for 3 days

- Adverse Events:

- Common: Headache, prolonged QTc (one of the measured ECG intervals important in heart conduction and rhythm synchronization), tachycardia (fast heartbeat).

- Common: Headache, prolonged QTc (one of the measured ECG intervals important in heart conduction and rhythm synchronization), tachycardia (fast heartbeat).

- Contraindications: Allergy to active ingredients or excipients, severe malaria (as per WHO definition), cardiac risks including congenital QTc prolongation, arrhythmias, severe hypertension, or heart failure, electrolyte imbalances such as hypokalaemia, hypocalcemia, or hypomagnesemia, use of QTc-prolonging medications like antiarrhythmics (e.g., amiodarone, sotalol), certain antibiotics (e.g., erythromycin, moxifloxacin), antifungals, and others, recent use of QTc-prolonging antimalarials such as mefloquine, chloroquine, or lumefantrine.

- Special Considerations:

- Pregnancy/ Breastfeeding: Shouldn’t be used.

- Children: Approved for children >6 months of age and >5 kg.

- Children: Approved for children >6 months of age and >5 kg.

- Precautions: ECG monitoring is advised in individuals at risk of QT prolongation (risk of life-threatening arrhythmia).

Not eating 3 hours before and after drug intake helps to avoid high peak levels of piperaquine, and may lower risk of cardial side effects. DHA-PPQ is highly effective and often preferred in regions with multidrug-resistant malaria.

- Cost: Not sold in the US, but generally cheap.

Summary

Your health and safety are essential, especially when traveling to malaria-endemic regions. This guide equips you with the basic knowledge to help you choose the right chemoprophylaxis or standby emergency treatment (SBET) for your trip.

There are still nuances and details that I couldn’t address in this post. Take the time to consult a travel health specialist and plan your prevention strategy based on your itinerary and personal health needs.

Remember, timely adherence to the prescribed regimen is just as important as choosing the right medication.

Check out my other blog posts for more tips and detailed advice on travel health. Your adventure awaits—stay safe and travel smart!

Resources

Travel Medicine, 4th Edition – December 13, 2018, Authors: Jay S. Keystone, Phyllis E. Kozarsky, Bradley A. Connor, Hans D. Nothdurft, Marc Mendelson, Karin Leder, Language: English, Hardback ISBN: 9780323546966

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023). CDC Yellow Book 2024: Health Information for International Travel. Oxford University Press.

Petersen, E. (2003). The safety of atovaquone/proguanil in long-term malaria prophylaxis of nonimmune adults. Journal of travel medicine, 10(suppl_1), s13-s15.

Overbosch, D., Schilthuis, H., Bienzle, U., Behrens, R. H., Kain, K. C., Clarke, P. D., … & Malarone International Study Team. (2001). Atovaquone-proguanil versus mefloquine for malaria prophylaxis in nonimmune travelers: results from a randomized, double-blind study. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 33(7), 1015-1021.

Nakato, H., Vivancos, R., & Hunter, P. R. (2007). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness and safety of atovaquone–proguanil (Malarone) for chemoprophylaxis against malaria. Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy, 60(5), 929-936.

Ringqvist, Å., Bech, P., Glenthøj, B., & Petersen, E. (2015). Acute and long-term psychiatric side effects of mefloquine: a follow-up on Danish adverse event reports. Travel medicine and infectious disease, 13(1), 80-88.

Overbosch, D., Schilthuis, H., Bienzle, U., Behrens, R. H., Kain, K. C., Clarke, P. D., … & Malarone International Study Team. (2001). Atovaquone-proguanil versus mefloquine for malaria prophylaxis in nonimmune travelers: results from a randomized, double-blind study. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 33(7), 1015-1021.

Petersen, K., & Regis, D. P. (2016). Safety of antimalarial medications for use while scuba diving in malaria Endemic Regions. Tropical Diseases, Travel Medicine and Vaccines, 2, 1-8.

Lalloo, D. G., Shingadia, D., Bell, D. J., Beeching, N. J., Whitty, C. J., & Chiodini, P. L. (2016). UK malaria treatment guidelines 2016. Journal of Infection, 72(6), 635-649.

Chiodini PL, Patel D, Goodyer L, Frise C, Mabayoje D, Aggarwal D. Guidelines for malaria prevention in travellers from the United Kingdom, 2024. London: UK Health Security Agency; October 2024.

Voumard, R., Berthod, D., Rambaud-Althaus, C., D’Acremont, V., & Genton, B. (2015). Recommendations for malaria prevention in moderate to low risk areas: travellers’ choice and risk perception. Malaria journal, 14, 1-7.

Schlagenhauf, P., Tschopp, A., Johnson, R., Nothdurft, H., Beck, B., Schwartz, E., … & Steffen, R. (2003). Tolerability of malaria chemoprophylaxis in non-immune travellers to sub-Saharan Africa: multicentre, randomised, double blind, four arm study. Bmj, 327(7423), 1078.

Ron Behrens, Standby emergency treatment of malaria for travellers to low transmission destinations. Does it make sense or save lives?, Journal of Travel Medicine, Volume 24, Issue 5, September-October 2017, tax034

https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/news-announcements/tafenoquine-malaria-prophylaxis-and-treatment

Disclaimer:

The information provided in this blog post is for general informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any health problem. The use or reliance on any information provided in this blog post is solely at your own risk.